Macro Themes for the '20s Cycle

Length of the cycle, still overweight the US, labor share of income recovery, structurally higher bond market volatility

This is the second of our three annual outlook notes, and because we tackle thematic investing, it is the most intellectually challenging and interesting (from our perspective) of the notes. Last year’s note covered the following themes:

• Echoes of the ‘60s

• Schumpeter’s Gale: The Pandemic

• Rebuilding the US Capital Stock

• Deglobalization, Collectivism and Mercantilism

• The End of the 39-Year Bond Bull Market

A year later, all of these themes are generally on track. Our ‘60s analog still looks appropriate, though the risk of skipping the early and mid-’60s and going straight to the ‘70s are non-trivial. The pandemic appears to have been a creative destruction accelerant, though aggressive policy is likely to result in a plethora of ‘zombie’ companies. A capital investment boom is underway, however a critical factor in this theme is the length of the business cycle. While 2021 was not a year of deglobalization and the US trade deficit hit record levels, supply chain disruption made the case for deglobalization even more compelling. Finally, nominal yields moved higher across the Treasury curve, however real rates are sharply lower in the front end of the curve and unchanged from 5 to 30-year maturities.

This year we focus on the length of the business cycle, whether we should stick with our long-standing overweight of US equities, the case for and implications of higher labor share of income and structurally higher bond market volatility and rates.

‘60s or ‘70: Length of the Cycle

From the end of WWII to JFK’s election during the first financial repression era there were five recessions. Two were related to war demobilization. The ‘49 recession followed an inflation shock when the CPI reached its all-time high of 19.7%, the combination of extreme inflation volatility and Truman’s reelection (The Fair Deal was concerning for the corporate sector) contributed to a sharp drop in capital investment. After the end of the Korean War, monetary policy played a major role in the end of six of the next seven business cycles. This gave rise to two competing movements: new-Keynesian economists who believed they could optimize the Phillips Curve tradeoff between employment and inflation, and monetarists who believed managing the Phillips Curve was a fool’s errand, arguing instead that policymakers should manage the monetary base. The Keynesians controlled the Fed in the ‘60s and ‘70s, however the Great Inflation led to the rise of Monetarism and Classic Economic Liberalism underscored by Nobel Prizes for F.A. Hayek and Milton Friedman. The shift in focus went from the inflation mandate in the ‘50s to the employment mandate in the ‘60s and ‘70s, then swung back to inflation in the ‘80s and ‘90s. During the ‘00s and ‘10s, globalization rendered the consumer price inflation mandate an afterthought, and two cycles ended with investment booms and busts. Those busts weakened Classic Economic Liberalism’s hold on the Fed and Keynesians regained control, ultimately leading to average inflation targeting, just as an OPEC Embargo level supply shock struck the world.

With Keynesians likely to strengthen their control over the Federal Reserve as the Biden Administration fills the open Governor spots, combined with a decade of private sector deleveraging and exceptionally weak capital investment during the ‘10s expansion, the most probable catalyst for the end of the ‘20s expansion is inflation and a delayed monetary policy response.

This brings us back to our ‘60s analog. In our recent note, Straight to the '70s?, we delve into the risk that the US economy moves from decades of disinflation to an inflation regime. In this scenario, despite the shift in the mandate weighting the Fed would likely end the cycle in the first half of the ‘20s. This is not our base case, we expect core goods inflation to fall from its current 9% level in 2022, however we expect its negative contribution of the last three decades to turn persistently positive. The more important question for the length of the cycle is whether the pandemic policy response, and the opening this created for progressives to take up where LBJ left off, will lead to significantly higher trend inflation for housing, healthcare, education and energy. Pushing in the opposite direction is an acceleration of technology innovation adoption in healthcare and education, work-from-home reducing housing costs as households are able to move out of high cost MSAs (metropolitan statistical areas), and shale energy capping the upside in oil and gas prices. Our base case is that trend inflation will settle in 2022-24 below 4%, a level we believe is a threshold that risks a wage price spiral like the late ‘60s. If this is correct, the cycle should extend until the second half of the ‘20s, allowing for a strong capital investment cycle.

Implementation of this Theme: Reasonably priced software, semis, industrial equities

The End of US Equity Market Outperformance?

We get asked this question every year, as a large percentage of strategists cannot resist the mean reversion temptation. While we respect those that argue that European, Japanese and emerging market indices weightings are more cyclical, and therefore more sensitive to the reflation theme than the US market, our interest in abandoning our long-standing US overweight ends there. Our first issue is that a key element of investing in non-US developed world markets is their banking system profitability, or actually lack thereof. Even at the peak of the ‘00s cycle when return on equity of European banks was higher than the US, their return on assets was half that of US banks, highlighting the even greater use of leverage. Regulatory and monetary policy in Europe, Japan and China as well as unrecognized loan losses in Europe and China are major impediments to non-US banks earning their cost of capital and contributing to an organic credit cycle.

In last week’s note, 2022 Outlook: Inflation Policy & Politics, we discussed the Mercantilists and whether deglobalization would prompt a change in export dependent economic models. Germany is likely to be the first mover: in the early ‘00s they restructured their labor laws to compete in the globalization boom and last week’s end of the Merkel era opens the door for a similar restructuring. China continues to struggle, and astute observers like Mike Pettis (“Trade Wars are Class Wars”) argue that export dependence is exacerbating imbalances and is an impediment to escaping the middle-income trap. In 2021, China’s trade surplus increased, and they allowed their exchange rate to appreciate due to outflow concerns emanating from General Secretary Xi’s war on tech titans ahead of the 2022 National Party Congress. Last week they took a step to stop the appreciation ahead of what is likely to be a shrinking trade surplus in 2022. These economic models are a drag on economic dynamism and make these markets a structural underweight until and unless policy changes.

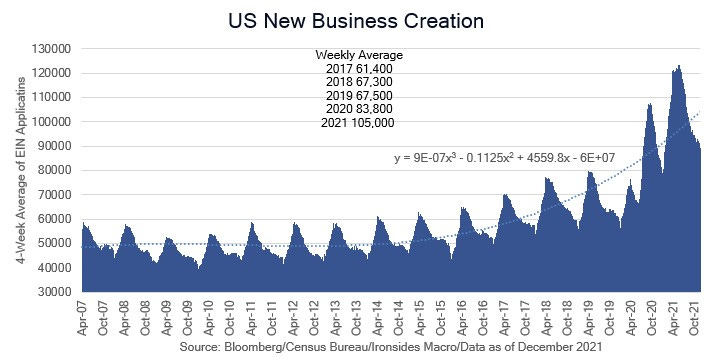

While we have cited reasons not to invest outside the US, the case for the US is perhaps best illustrated by the response to the pandemic by the small business sector and the public at large. Small business hiring has exceeded large businesses despite early pandemic policies that favored large businesses. New business creation is running far above pre-pandemic levels and labor dynamism improved decidedly. While big tech argues that China is ahead of the US in AI, 5G, and semiconductor production, technology incremental innovation (improvement) diffusion is accelerating in the US — as illustrated by the US in the upper right quadrant of a plot of productivity and per capita GDP with China in the lower left corner. We are sticking with our US overweight.

Implementation of this Theme: Overweight US equities, underweight export dependent economies - China, Germany, Japan, South Korea

Power to the People

Last week’s data included the lowest number of weekly initial claims since 1969 and the widest gap between job openings and hirings in the 20-year history of the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). The Atlanta Fed Wage Prime Age Wage Tracker increased 4.5% in November from 4.2% in October, the fastest rate since 2001 and the differential between the lowest and highest quintile is at the highest level since 1998 (2.4%) prior to the China labor shock. The prior week’s employment report had the second largest number of worker flows from not in the labor force to employed, only surpassed by May 2020 in the depths of the pandemic in a series that began in 1990. 3Q21 Unit Labor Costs and the Employment Cost Index Private Sector Wages and Salaries surged 6.3% and 4.6% year-on-year. The Kansas City Fed Labor Conditions Index is at a record level. Deere employees conducted a strike and won significant concessions and Starbucks employees in Buffalo voted to unionize. Our labor slack composite, despite decent weightings in participation rates, has fully recovered from the pandemic shock.

In their book The Great Demographic Reversal, Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan detail the impact of the integration of China, and to a lesser extent, the Soviet Bloc, into global supply chains on the developed world labor markets from 1990 until the 2010’s. In the postscript, they discuss the pandemic and the acceleration of trends including higher inflation and developed world labor share of income as the China shock dissipated. Labor share of income for nonfinancial corporates was stable in a range between 61% and 66% from the ‘60s through the ‘90s before plunging to a low of 57% in 2014. Pre-pandemic labor share had recovered to 60%, the pandemic caused a brief spike to 65%, and as of 3Q21 it is 60% and likely headed higher.

Before concluding a wage/price spiral that impairs corporate margins is imminent, keep in mind our work on labor market dynamism. The first order effect of reallocation is higher wages, the secondary impact is faster productivity growth. Productivity is notoriously hard to measure in real time, partially because it is a residual between hours worked that we have decent data on, and output that the Bureau of Economic Analysis struggles with. Nonetheless, corporate margins are a decent proxy for productivity. If wages and prices are rising, but margins hold up as we expect, then increased labor dynamism is boosting productivity. This is another critical factor in the length of the expansion.

Implementation of this Theme: Reflationary sectors with operating leverage, financials, energy, industrials, materials

The Natural Rate of Interest

Our fundamental basis for expecting a higher terminal funds rate and neutral or natural rate (r* in Fedspeak) is built on changing global and domestic (life cycle consumption patterns) demographics, technology diffusion slowing in three large sectors due to public policy, and public sector debt inflationary implications. In a call last week, a client questioned our assertion that we did not reach the endogenous neutral rate in 2018 because housing activity slowed that year. Given that housing is the most rate sensitive sector this is crucial to our view, in our note Housing: Another Echo of '88, April 2019, we made our case that the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act, like the 1986 Tax Reform was the primary cause of the slowdown in housing activity (supported by academic research). When TCJA passed, a notable housing economist was projecting a 10% drop in house prices due to the increased standard deduction that diluted the mortgage interest deduction for lower price homes, and the SALT cap reduced the attractiveness of mortgage interest for higher price homes. Instead, the Core Logic 20-City Index slowed from 6.2% appreciation to 4.0% in 2018 and kept declining to 2.8% by the end of 2019 even as housing activity rebounded even more vigorously in 2019 than it did in 1988. Housing starts and new home sales had similar declines in both ‘87 and ‘18, both rebounded sharply the following year though the ‘19 recovery was stronger. The slowdown was a transitory reaction to tax policy and had little to do with monetary policy.

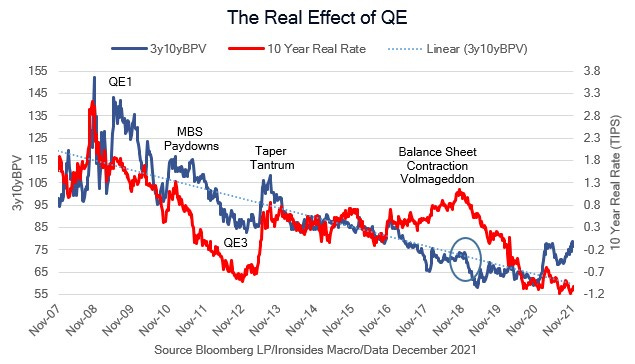

As 2021 draws to a close, the nominal Treasury curve is flattening ahead of an FOMC meeting when the Committee has effectively preannounced an acceleration of the reduction of asset purchases (the taper). The impact of both the stock and flow of Fed purchases is evident in the real rates curve (inflation protected securities). The only part of the curve that has moved higher from the June FOMC meeting, when the Fed began providing ‘advanced notice’ of the taper, to the September FOMC preannouncement and November formal notification are 5-year rates. The front end of the curve is below, and long-end is at the same level as the August 2020 low in nominal 10-year rates. The 2s10s term premium curve has flattened since the November FOMC as well, which highlights the lack of risk premium for holders of longer duration Treasuries. In other words, while the Fed is attempting to tighten, policy is easing. This largely explains why the ‘optionality assertion’ is likely to be exercised to accelerate the pace of reduction of asset purchases at next week’s FOMC meeting. While the summary of economic projections is likely to show an earlier start and steeper path for the policy rate, step number two should be going directly to ending reinvestment of Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities. This was not the ‘10s sequencing, but this change in process would steepen the curve, improve bank profitability and potentially dampen a white-hot housing market. The ‘04-’06 ‘Conundrum’ that ended when the Japanese ended QE in 2Q06, but came too late to avoid a housing crash, should dissuade the FOMC from repeating the mistakes of the past.

One way or another we expect the Fed’s role in the suppression of real rates and implied volatility to dissipate in the ‘20s. We believe rates volatility is likely to be structurally higher in the ‘20s for three reasons. The first is the Fed’s stock and flow of the largest source of rates implied volatility, mortgage prepayments. Secondly, regulatory policy has forced market making outside of the banking system, and what remains is constrained by policy including supplementary leverage ratios, high quality liquid asset (HQLA) requirements, and so on. (For some additional background, see former Fed Vice Chair for Supervision’s departing thoughts.)

A similar dynamic unfolded in equity markets that migrated market making from large broker dealers to high frequency traders, and the effect was higher volatility of volatility (volatility shocks). The final, and most important element is greater fundamental volatility due to the end of decades of disinflation. In short, the private sector can withstand higher rates than the last cycle, policy is likely to be both less directly interventionist and more tolerant of higher inflation and structural volatility will increase the risk premium of holding long duration. The stock/bond correlation is headed down a similar path to the ‘60s when rates and equities rose together.

Implementation of this Theme: PFIX (Simplify ETF is long rates volatility), yield curve steepeners, IAT (regional bank ETF)

Barry C. Knapp

Managing Partner

Director of Research

Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC

908-821-7584

bcknapp@ironsidesmacro.com

https://www.linkedin.com/in/barry-c-knapp/

@barryknapp