Overly Restrictive

Macro pru and the last war, Europe's profitability problem, the data doesn't justify 50 even if, what if the Fed doesn't read the room

Rate Risk

The banking crisis was not resolved by last weekend’s macro prudential policy, it is clear to us that policy is now overly restrictive, perhaps not to the household sector, at least yet, but the banking system is in a world of hurt. Fortunately, this is an easier problem to solve than in 2008, assuming the FOMC can read the room. In last week’s note, Malinvestment in Silicon Valley, we walked through Fannie Mae’s wild duration ride in 2002 that led to ‘regulatory reform’ that effectively shut the interest rate risk barn door after the horses ran out, only to run into a credit risk tornado. The financial crisis led to the opposite reaction: Dodd Frank and perhaps more significantly, Basel ‘risk-based’ capital rules reduced credit risk in the banking system, leading to a period of financial repression that left the banking system with massive rate risk. The Fed’s portfolio mark-to-market is ugly, with 5-year USTs issued in ’21 trading around 90, and the 65% of their Fannie, Freddie and Ginnie 2 and 2.5 coupons at trading at 80 and 85 respectively. Recall in ‘21 the Fed purchased $969 billion of USTs with an average of 6 years and $529 billion of agency mortgage-backed securities, while commercial bank purchases were nearly identical in size. A back of the envelope on the Fed purchases is -$190bn.

Bank portfolios look like the Fed’s; this explains why the street was so supportive of the Fed’s tightening strategy primarily focused on rate policy with passive QT. In “Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs?”, the authors concluded, “The U.S. banking system’s market value of assets is $2 trillion lower than suggested by their book value of assets accounting for loan portfolios held to maturity. Marked-to-market bank assets have declined by an average of 10% across all the banks, with the bottom 5th percentile experiencing a decline of 20%.” Additionally, there were 500 banks with deeper securities losses than Silicon Valley Bank.

We suspect neither the Fed nor large banks considered the implications of a deeply inverted yield curve combined with massive securities portfolio losses. While we were arguing for policy tightening similar to the pandemic easing process, with active QT and a slower rate hike path that would have kept an upward slope to the yield curve and directly impacted housing without blowing up bank balance sheets, street economists were validating the Fed’s ill-advised passive QT and aggressive rate hikes. This is perhaps because they thought the Fed was unlikely to tighten beyond the ~3% policy rate level that would flip carry on the Fed and bank balance sheets, negative.

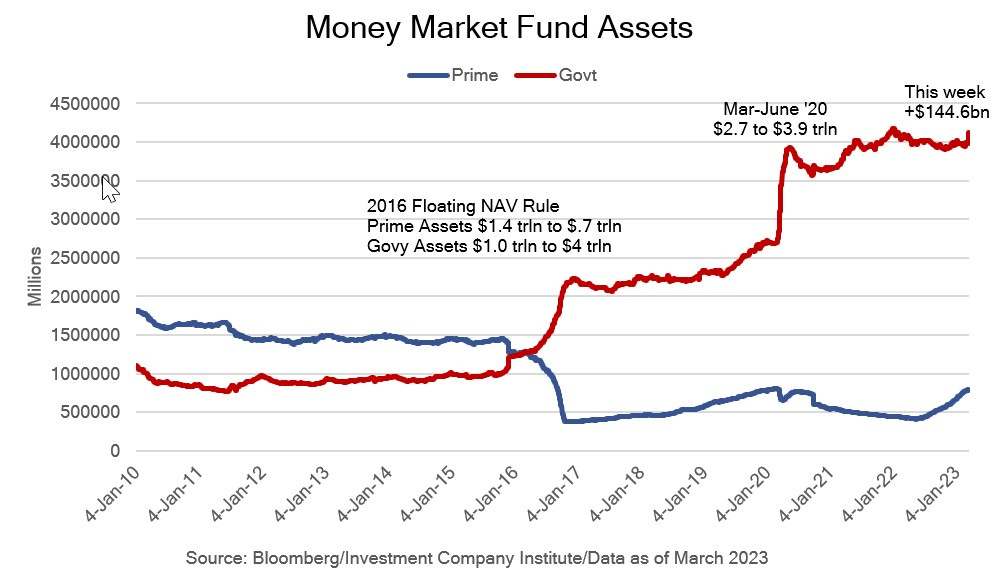

As we detailed last week, the $1.5 trillion of bank reserves created by Fed asset purchases and $1.7 trillion from the Treasury drawing down their account at the Fed (TGA) primarily through reduced issuance, combined with the end of the cash and Treasuries exemption from the supplementary leverage ratio, directed those deposits from large GSIB ‘safer’ hands to smaller banks. One issue we would add to the Silicon Valley Bank saga was the Wells Fargo asset cap — they are largest small and medium business lender in California. This week, discount window borrowing surged $148.3 billion to $152.9 billion, the Fed’s new bank term funding program (BTFP) took in $11.9 billion and there was another $132 billion of loans to FDIC bridge banks. Inflows to government money market funds were $144.6 billion this week. While some have characterized the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet as reversing 60% of QT, we wouldn’t go that far. From the perspective of the three QE/QT channels — liquidity, duration and interest rate implied volatility/mortgage prepayment risk — the injections are intended to be temporary liquidity injections, have no duration or volatility implications and will likely remain trapped in the banking system.

The Fed, Treasury and FDIC took extraordinary actions to guarantee uninsured depositors of Silicon Valley and Signature Banks and arranged a support program for First Republic using systemic risk legal provisions. In a systemic risk crisis, attempts to separate macro prudential and monetary policy are reckless and naive. The Fed needs to pause the rate hikes and provide guidance that the balance of economic and inflation risk is now skewed to the downside; in other words conditions are more than sufficiently tight. FOMC participants need to think very carefully about their forecasts. The September SEP (summary of economic projections) was a time bomb that blew up the yen, pound, euro, yuan and mortgage market. While this all sounds dire, it is still possible to get back on the ‘95 analog track; the Fed can resolve rate risk with monetary policy, unlike the ‘08 credit crisis when monetary policy was little more than a Band-Aid. FOMC participants will be reluctant to clean up their mess using monetary policy, but macro prudential policy is always fighting the last war.