Macro Trends for 2020 & Beyond

Deglobalization, China, Innovation, Energy Stability and Rate Suppression

This is lengthy thematic note we are making available to all of our subscribers, we hope one of your new year’s resolutions will be a paid subscription to Ironsides Macroeconomics, “It’s Never Different This Time.”

In the second part of our 2020 outlook process, we are going to focus on long-term thematic, secular, and most importantly, investable trends. In last week’s note we covered three cyclical tailwinds – a recovery in global exports and manufacturing, increasing monetary policy liquidity and the strongest real wage growth for the cycle – we expect to exert a strong influence on risky assets for the first third of 2020. We then expect the ninth monetary policy normalization shock of the cycle followed by a recovery and broad range with a marginal upward bias for US equities and rates through the election. We remained bullish cyclical US equities in 2019 with the exception of a 6-week period from the beginning of August through the middle of September. We expect 2020 to require more tactical and structural changes to asset and sector allocation. Nevertheless, identifying thematic, secular, investable trends is even more critical than any tactical asset and sector allocations. In this note we cover five somewhat interrelated themes; deglobalization, China’s inability on their present course to escape the middle income trap, innovation adoption in the healthcare sector, a more stable environment for energy companies and interest rate suppression and the demand for capital.

Deglobalization

One of our three key tailwinds for early 2020 is a recovery in global exports and manufacturing. While recent data and policy developments are supportive of our recovery forecast, the secular trend of deglobalization is being driven by inexorable economic market forces rather than the highly visible, and controversial, political markets. Two studies were particularly impactful in formulating our views on this topic; the first is “Demographics will reverse three multi-decade global trends”, Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan. Rather than paraphrase, here is the abstract to this fascinating paper.

Between the 1980s and the 2000s, the largest ever positive labour supply shock occurred, resulting from demographic trends and from the inclusion of China and eastern Europe into the World Trade Organization. This led to a shift in manufacturing to Asia, especially China; a stagnation in real wages; a collapse in the power of private sector trade unions; increasing inequality within countries, but less inequality between countries; deflationary pressures; and falling interest rates. This shock is now reversing. As the world ages, real interest rates will rise, inflation and wage growth will pick up and inequality will fall. What is the biggest challenge to our thesis? The hardest prior trend to reverse will be that of low interest rates, which have resulted in a huge and persistent debt overhang, apart from some deleveraging in advanced economy banks. Future problems may now intensify as the demographic structure worsens, growth slows, and there is little stomach for major inflation. Are we in a trap where the debt overhang enforces continuing low interest rates, and those low interest rates encourage yet more debt finance? There is no silver bullet, but we recommend policy measures to switch from debt to equity finance.

https://www.bis.org/publ/work656.pdf

Before we read, and later met with Dr. Goodhart during our tenure at BlackRock in 2015, a Barclays salesperson in Paris sent us a report in 2012 from the Boston Consulting Group called “U.S. Manufacturing Nears the Tipping Point”. In this report BCG identified seven industry groups that accounted for $200 billion of Chinese imports where the cost advantage of outsourcing was gone due to markets closing the gap between unit labor costs, rising transportation costs, and the U.S. energy revolution, while exchange rate and supply chain risks were increasing sharply.

Figure 1: The OECD competitiveness index illustrates a long period of unit labor cost convergence between the US and Germany on the high side and China from below.

Since BCG’s report seven years ago, unit labor costs continued their convergence (figure 1); the US has become the world’s largest producer and a net exporter of energy. The Chinese Central Committee depressing their currency nearly broke open their closed capital account in August 2015. Transportation costs are likely to rise further as excess capacity from the pre-crisis shipbuilding boom in China, South Korea and the Mid-East dissipates and the 2020 International Maritime Organization shipping fuel standards begin. Finally, we spent some time recently with a CEO who competed directly with Huawei and negotiated with ETSI on 4G standards. We discussed our interpretation of Liu He’s recent essay in the People’s Daily where he proposed increased penalties for intellectual property theft. The CEO provided no pushback against my thesis that in a central committee totalitarian political system, the rule of law is whatever the ideology and expediencies of central committee members decides it is. He added that Huawei has evolved to the point where they have IP they created to protect themselves. Consequently, the Trump administration may get Chairman Xi’s signature on a trade deal, however, US companies have paid a large price for access to what was once, but no longer is, inexpensive Chinese labor. While US corporates will pay for access to the second largest consumer market, they are unlikely to invest in China with the reckless abandon as they did in the globalization boom of the ‘90s and ‘00s.

This week the British provided Boris Johnson a decisive majority that is likely to facilitate leaving the highly regulated EU system. In essence, the UK has rejected the modern manifestation of Joseph Schumpeter’s prophecy of elite technocrats supplanting entrepreneurs. Schumpeter considered that ‘forecast’ with social democracy’s failure in the ‘70s. The Brits rejected EU for the same reason the labour party was crushed, memories of British socialism in the ‘70s. Within the EU, Germany’s massive current account surplus is the source of instability and will likely be an issue the Trump administration focuses on in 2020. South Korea and Japan are engaged in a trade skirmish. US actions have weakened the WTO, and like GATT and Bretton Woods, these multilateral organizations proved incapable of addressing trade imbalances that whatever the cause and effect, have always been politically toxic. Goodhart and Pradhan’s labor supply shock is behind us; in its wake are massive imbalances and the associated political backlash. A bounce in global trade is likely over the next six months, however, the magnitude is probably will be disappointing and then the deglobalization trend will continue through the 2020’s. The production model of US industrials, and increasingly through the ‘20s technology manufacturers, will be to produce where final demand resides. Supply chains that capitalize on cheap abundant labor are passé. Labor share of income in the US has increased 3 1/2% since the 2014 low, it is likely to return to the pre-globalization trend in the ‘20s.

http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2019-11/22/nw.D110000renmrb_20191122_1-06.htm

Figure 2: Labor share of income has improved significantly from the low, we expect it to continue to increase in the ‘20s absent any direct interventions from the heavy hand of government.

Capitalism, Socialism and Mercantilism

Socialism with Chinese mercantilist characteristics is in a decline that without true reform, could see the end of the Mao dynasty in the ‘20s. On September 28, 2019 we wrote a report (link below) detailing our view that the Chinese political and economic systems – socialism and mercantilism – would fail as they have in every other nation that has adopted these political economic systems. Chairman Xi’s regime has moved away from what F.E. Hayek called the spontaneous economic order and is increasingly more reliant on centralized control over the means of production. China is resource starved and likely to run current account deficits for decades requiring an open capital account they have shown no indications they will risk opening. The UN forecasts a doubling over the next 20 years in their demographic dependency ratio – the percent of non-working over working age population. There has been two major macroeconomic shocks in the last five years, a heavy industry hard landing from 2014-2016 and the more recent export sector slump. During the initial shock, Chinese ordinary imports – our preferred measure for China’s external impulse – fell from +20% to -20%, during the second shock following stimulus that set aside economic rebalancing, ordinary imports dropped from 20% to -7%. Earnings of the state owned enterprise laden Shanghai Composite index dropped from +10% to -20% during the 2014-16 episode and from +10% to -4% during the export bust. We see no evidence that the system as currently constructed or policy reaction function to these rolling crises, will facilitate escaping the middle-income trap. Consequently, we know many will be tempted by the allure of the second largest consumer market; however, generally we do not get long cyclical counter trend bounces and cannot foresee investing in China.

Figure 3: One of our favorite charts, total factor productivity and per capita GDP. This is the wealth of nations.

https://ironsidesmacro.substack.com/p/capitalism-socialism-and-mercantilism

Profit Margins & Innovation Adoption

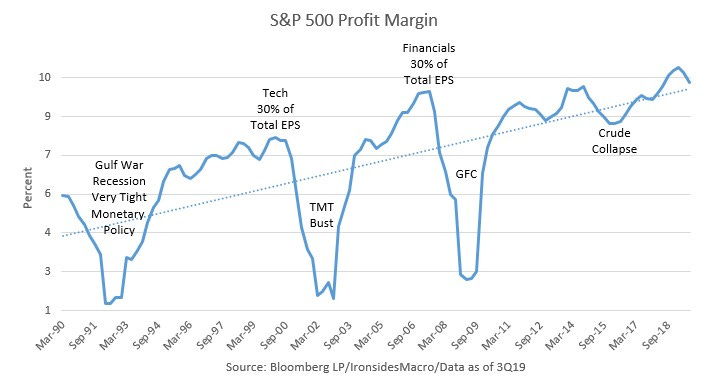

Figure 4: S&P profit margins have made higher highs and higher lows each full and mini-cycle for three decades.

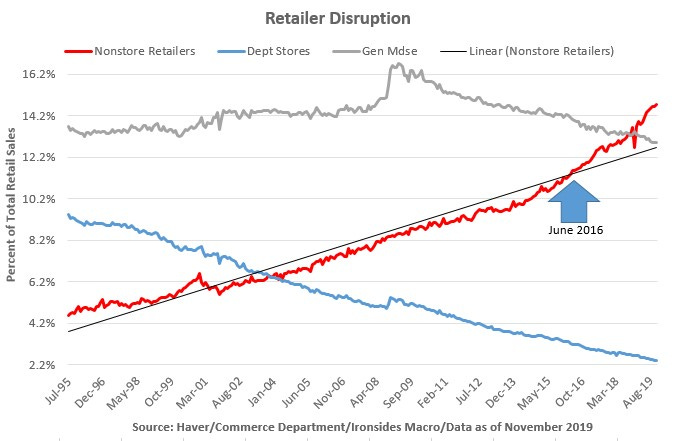

If S&P 500 profit margins are mean reverting, it is around a persistent multi-decade uptrend. We believe productivity is the driver and the reason the Bureau of Economic Analysis believes productivity is weak is they underestimating IP investment, and overestimating technology prices. In Alexander Field’s, “A Great Leap Forward” he detailed the long process of diffusion of 1920’s innovation during the was masked by the Great Depression and delayed by WWII, and finally became evident in the ‘50s and persisted until the first OPEC embargo in ’73. He went on to show how the ‘90s technology boom appeared to boost productivity growth in just three sectors, technology, telecom and finance. Another interesting and relevant conclusion of his work on the history of productivity was the positive impact of economic contractions. In a version of creative destruction, Field observed that business processes were more likely to change and adopt innovation in recessions. We see strong similarities this cycle, during the deleveraging stage of the post-crisis expansion through mid-2014, slack final demand obfuscated the effects of software, cloud mobility and a host of productivity enhancing software investment. Meanwhile, smartphones and tablets were simultaneously destroying a range of industries while allowing us to ‘work’ at all hours wherever we happened to be, thereby deepening the productivity mystery. After the 75% oil price collapse began in mid-2014, the trend in real consumer spending improved from 2% to 2 ¾% and while a rising tide should have raised all boats, instead the ‘Retail Armageddon’ accelerated underscoring the impact of technology adoption. Labor market dynamism recovered rapidly, employment for less-skilled workers increased sharply; profit margins went to another all-time high and in 2018 productivity growth finally improved.

Figure 5: We added a trendline to show the acceleration of internet sales market share in 2016 as the trend consumption improved.

As we consider the outlook for productivity over the coming decade we are focused on one of the eleven S&P economic sectors that has been the largest drag; healthcare. Margins have been trending lower for three decades while the sector grows ever larger in terms of total economic expenditures. Like retailing, anecdotal evidence is building that technology adoption in healthcare is accelerating. While the 1.4% margin improvement from the June 2018 low is a small fraction of the 10% decline from the 15% 1995 peak, there is evidence in the labor market that the sector is becoming more dynamic. The unprecedented gap between job openings and hiring in the job openings and labor turnover series is attributable to three sectors, manufacturing, financial and healthcare. Healthcare is the vast majority, however until 2014 worker reallocation – the quarterly sum of hiring and separations as a percent of total employment – was trendless. In 2014 the openings gap increased sharply, worker reallocation followed and by early 2016, an uptrend in wage growth began.

Figure 6: When we first built the chart on healthcare margins we were shocked, we looked at the underlying industries and the pressure has been pretty widespread. The sales per employee chart is new, and implies the sector might be in the early stages of less labor intensity.

Margins are attempting to bounce, labor market dynamism and wages are rising. We expect a more dynamic labor force and technology investment to improve productivity over time though initially the growth in the labor force reduced sales per employee. The existential threat of universal healthcare should be a forcing mechanism as well. Whatever the catalyst, increased healthcare productivity is crucial in the ‘20s, without it, there is likely to be a government takeover and rationing.

Figure 7: Not shown here are the underlying components of reallocation, hiring is up and so are voluntary separations (quits). The gap implies the healthcare labor market is tight and that is why wages are going up, our other work hints productivity may be contributing to the increase.

Energy & ESG

We went to two dinners this week where ESG and the related flows were a topic of discussion. Our graduate studies in the late ‘80s were at a university that emphasized total quality management theories of W. Edwards Deming and Joseph Juran. In other words, quality management is not a new concept. In our view, ESG is the inevitable attempt to quantify the quality of business management. It is a worthy goal, however practically speaking; the proliferation of this investing framework has led to divestment of the energy sector due to concerns about the role of fossil fuels in climate change. Given the outlook for oil and natural gas in total energy generation for the next couple of decades, removing energy from your investable universe is likely to reduce returns. In our experience, money flows have little forecasting value for equity investors, they are explanatory at best and often a contrarian indicator. The energy sector struggled this year for two primary reasons, excess capacity and the global trade and manufacturing recession. In other words, ESG investors who restrict energy investments outperformed for reasons having little to do with their process.

Figure 8: Energy has been the major source of price instability since the ‘70s when the Fed began removing it to better analyze the trend. Perhaps they should refocus on headline prices.

Technology innovation changed the elasticity of supply for oil and gas profoundly. Investors underappreciated this change; it implies greater inflation stability, and ultimately more stable cash flows to energy companies. Before we get to the point where stability of cash flows is rewarded by investors, excess exploration capacity and investment capital, delivery bottlenecks and the global manufacturing recession impact on global energy demand needs to bottom out. The oil market’s three non-recessionary oil price collapses over the last four decades are illustrative. The mid-‘80s collapse was preceded by a 4-5 million barrel per day (bpd) increase in non-OPEC supply and triggered by a weakening of demand that proved transitory. Global demand was approximately 45 million bpd and excess capacity was 4 million, prices did not recover to their old highs until Iraq invaded Kuwait four years after prices bottomed in ’86. The late ‘90s slump was also preceded by a 4-5 million bpd increase in supply, global demand was above 60 million and excess capacity was less than 2 million bpd. Prices recovered within a year. The effect of technology on the 2014-16 collapse is clear when you consider a 90+ million bpd market, excess capacity of less than 1 million and prices nowhere close to the pre-crash high four years later. Like the late ‘90s episode a flattening, but not outright decline, in Asian demand was the trigger event. Looking into the next decade, we expect electric vehicles to facilitate integrating natural gas into the transportation system, infrastructure will further dampen volatility and stabilize prices and the boom/bust nature of the industry will dissipate. In short, energy investors will go through a similar evolution to the financial sector post-financial crisis, where stability of earnings at lower levels of profitability took the better part of a business cycle to be rewarded with decent relative performance.

Interest Rate Suppression

This is another topic where Goodhart and Pradhan’s analysis of the 20 year 120% increase in the supply of global industrialized labor is helpful. As labor replaced capital and savings in the emerging world grew as the population in the develop world increased, the ‘natural rate’ (r* as the ‘Federalies’ call it) of interest fell. Goodhart and Pradhan concluded those forces are largely behind us and that demand for capital would slowly begin to drive r* higher. We agree with their thesis and would add a couple of complexities that we suspect is the reason why the unobservable r* and market real interest rates have not yet begun to increase. The first partially explains the second, excess global manufacturing capacity from the golden age of globalization and mercantilist economic systems in China, Germany, Japan and much of the emerging world structured to capitalize on export growth twice the world GDP, and central bank policies. If we then consider the US demand for capital, the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA) had little or no effect on the cost of capital for equipment investment, but did significantly reduce the after-tax cost of capital for debt financed structures investment and equity financed intellectual property. If our deglobalization or BCG’s U.S. manufacturing renaissance views are correct, demand for structures investment capital that fell sharply during the golden age of globalization, is likely to increase. While there was an initial 13% increase in 1H18 following the passage of TCJA, structures investment weakened considerably alongside business confidence during the Trump trade war. Consequently, with investment weak in the mercantilist world and in the US concentrated in equity financed IP, the inflection point where private sector demand for capital has been delayed until the ‘20s.

Figure 9: High correlation of the components of inflation in the ‘70s implied endogenous factors like slack had a broad effect on prices. The correlation is currently zero indicating exogenous, and we believe non-monetary, factors are suppressing prices.

Meanwhile the demand focused new-Keynesian economics controlling the means of exchange (central banks) are constrained by mandates developed during the Great Inflation when endogenous factors, primarily labor market slack, played a dominant role in consumer prices. We look at inflation differently, the correlation of the major components of CPI and standard deviation of both headline and core are at multi-decade lows. We view these measures as confirmation that labor market slack is not a significant factor in consumer prices, instead non-monetary factors including increased elasticity of energy supply, technology innovation adoption in services and global excess goods capacity explain ‘lowflation’ and stable prices. Consequently, unconventional monetary policy – quantitative and credit large-scale asset purchase programs, negative rates, targeted lending schemes and forward guidance – interfere with the capital allocation process thereby impairing creative destruction, reduce credit supply by weakening bank profitability and create liquidity traps and increase household savings.

Figure 10: Notice the sharp drop in rates in August and reversal in September with implied volatility of an option with a similar term as a mortgage. The latest move up in rates on trade news led to lower implied volatility. We expect structurally higher volatility in the ‘20s as central banks reduce their intervention.

Before we offer some thoughts on the longer term there is a not-so subtle process underway in the US where the Federal Reserve is transferring the greatest source of interest rate volatility back to the private sector. The US 30-year fixed rate mortgage is a fairly unique product globally, given the size of the US housing stock, the option to prepay without penalty causes high velocity movement in underlying rates. During the 2010-2017 period when the Fed purchased 30% of the outstanding stock of agency mortgage-backed securities and did not hedge interest rate risk, the relationship between rates and implied volatility was reversed as Fed purchases drove rates and volatility lower. In 2019, after the Fed had reduced their mortgage holdings by $300 billion to $1.5 trillion, the market resumed its traditional relationship as evidenced by a 45 bp drop in rates following President Trump’s decision to increase tariffs on August 1 and a quick 40 bp reversal in September as trade tensions eased. Volatility increased during the drop and increased during the increase. Even with the Fed’s ‘not QE’ $60 billion per month of Treasury bill purchases they are allowing $20 billion of mortgages to run-off each month. When they stop purchasing bills in June, the transfer of interest rate volatility risk will be increasingly evident. With the worst of the confidence shock from the trade war in the past, even with election-year policy uncertainty, we expect the demand for capital to be increasing and r* to begin its inevitable grind higher. For the central banks of the mercantilist world to end their rate suppression, the political class will have to accept that their business model is antiquated. We expect Germany to be the first mover, most likely following a disappointing recovery in exports. If their first attempt is fiscal stimulus in the form of government spending, they will fail. Germany requires a restructuring of their tax code to incentivize innovation, in other words fewer autos, more software.

Next week we will write a note summarizing 2019, in the subsequent weeks over the holidays we will keep our notes brief. We hope you found our attempt to identify thematic secular trends thought provoking.

Reading List

“The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers”, Paul Kennedy

“Capitalism in America, A History”, Alan Greenspan & Adrian Woolridge

“Diversity Explosion, How New Racial Demographics are Remaking America”, William H. Frey

“Clashing Over Commerce, A History of US Trade Policy”, Douglas A. Irwin

“1493, Uncovering the New World Columbus Created”, Charles C. Mann

“Destined for War, Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap”, Graham Allison

“A Great Leap Forward, 1930s Depression and US Economic Growth”, Alexander J. Field

“The Constitution of Liberty”, F.A. Hayek

“Judgement in Moscow, Soviet Crimes and Western Complicity”, Vladimir Bukovsky

“1931, Debt, Crisis and the Rise of Hitler”, Tobias Straumann

My next book: “Great Society, A New History”, Amity Shlaes

Barry C. Knapp

Managing Partner

Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC

908-821-7584

https://ironsidesmacro.substack.com

https://www.linkedin.com/in/barry-c-knapp/

@barryknapp

This institutional communication has been prepared by Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC (“Ironsides Macroeconomics”) for your informational purposes only. This material is for illustration and discussion purposes only and are not intended to be, nor should they be construed as financial, legal, tax or investment advice and do not constitute an opinion or recommendation by Ironsides Macroeconomics. You should consult appropriate advisors concerning such matters. This material presents information through the date indicated, is only a guide to the author’s current expectations and is subject to revision by the author, though the author is under no obligation to do so. This material may contain commentary on: broad-based indices; economic, political, or market conditions; particular types of securities; and/or technical analysis concerning the demand and supply for a sector, index or industry based on trading volume and price. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. This material should not be construed as a recommendation, or advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any investment. The information in this report is not intended to provide a basis on which you could make an investment decision on any particular security or its issuer. This material is for sophisticated investors only. This document is intended for the recipient only and is not for distribution to anyone else or to the general public.

Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although such information is believed to be reliable, no representation is made is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of such information. This information may be subject to change without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics undertakes no obligation to maintain or update this material based on subsequent information and events or to provide you with any additional or supplemental information or any update to or correction of the information contained herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates and partners shall not be liable to any person in any way whatsoever for any losses, costs, or claims for your reliance on this material. Nothing herein is, or shall be relied on as, a promise or representation as to future performance. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS.

Opinions expressed in this material may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed, or actions taken, by Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates, or their respective officers, directors, or employees. In addition, any opinions and assumptions expressed herein are made as of the date of this communication and are subject to change and/or withdrawal without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may have positions in financial instruments mentioned, may have acquired such positions at prices no longer available, and may have interests different from or adverse to your interests or inconsistent with the advice herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may advise issuers of financial instruments mentioned. No liability is accepted by Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates or partners for any losses that may arise from any use of the information contained herein.

Any financial instruments mentioned herein are speculative in nature and may involve risk to principal and interest. Any prices or levels shown are either historical or purely indicative. This material does not take into account the particular investment objectives or financial circumstances, objectives or needs of any specific investor, and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, investment products, or other financial products or strategies to particular clients. Securities, investment products, other financial products or strategies discussed herein may not be suitable for all investors. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities, investment products or other financial products mentioned herein.

The material should not be provided to any person in a jurisdiction where its provision or use would be contrary to local laws, rules or regulations. This material is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose absent the written consent of Ironsides Macroeconomics.

© 2019 Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC.