Capitalism, Socialism and Mercantilism

Adam Smith's invisible hand is solving the 'China problem'

We are making this note available to both paid and free subscribers. In the note we make our case that, while the political consensus that we should be ‘doing something’ about China is bipartisan, in our view ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ is in the process of failing just as every other statist and mercantilist economic system has.

Graphic is courtesy of Bloomberg made for an October 10, 2019 appearance on ‘The Open’

“Political leaders in capitalist countries who cheer the collapse of socialism in other countries continue to favor socialist solutions in their own. They know the words, but they have not learned the tune.”

- Milton Friedman, Rose Friedman (1990) “Free to Choose”

In 1942, Joseph Schumpeter wrote “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy”. This note is not a critique of Schumpeter’s premise that there is a long-run tendency for profits to vanish, rather my assessment that the bipartisan position that something needs to be done about China by policymakers, ignores the market forces that have administered two malinvestment busts in 5 years to the largest command and control system in history. Critics who would be quick to site the failures of socialism or mercantilism, seem to believe that China is different from all the other command and control or export dependent nations that preceded them.

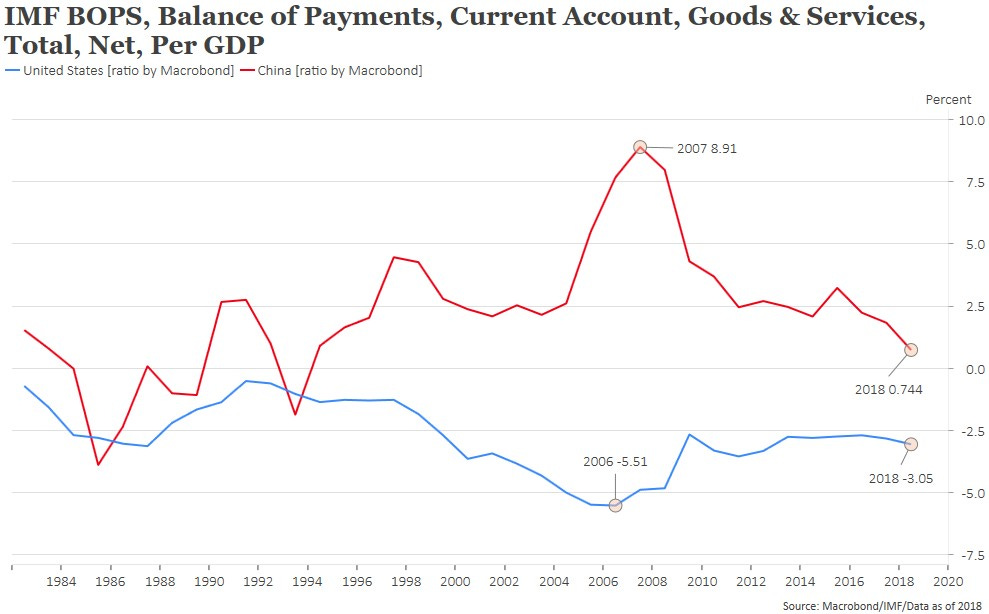

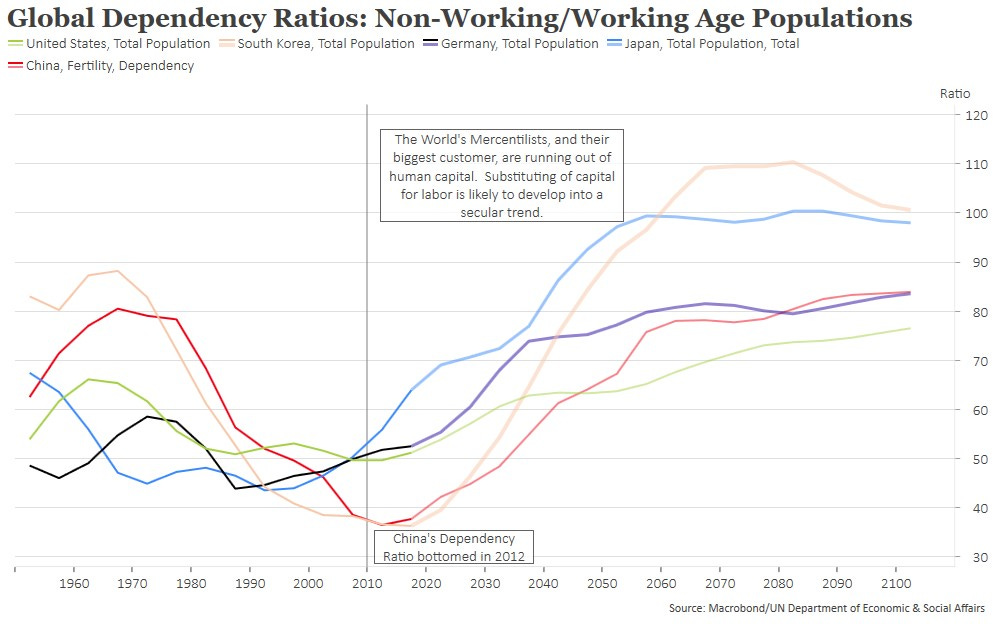

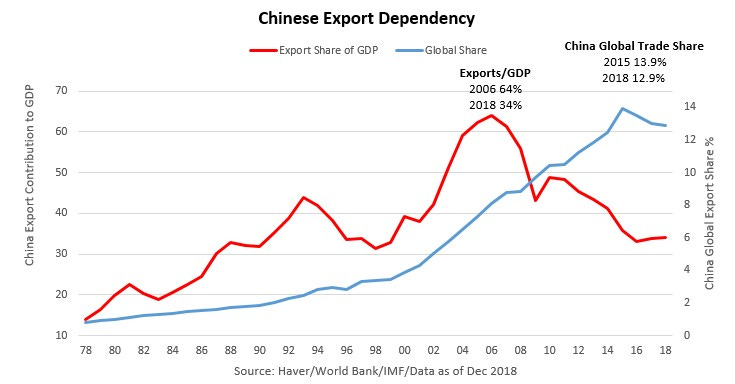

We see quite the opposite, China’s current account as a percent of GDP has contracted sharply since the pre-Global Financial Crisis high at 9% of GDP and is now close to zero. China’s global trade market share peaked in 2015, shortly after their demographic dividend that created the greatest increase in the supply of labor in history, and been steadily contracting.

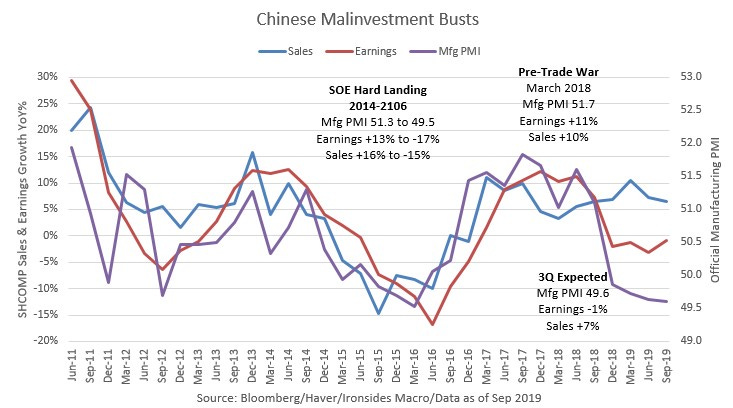

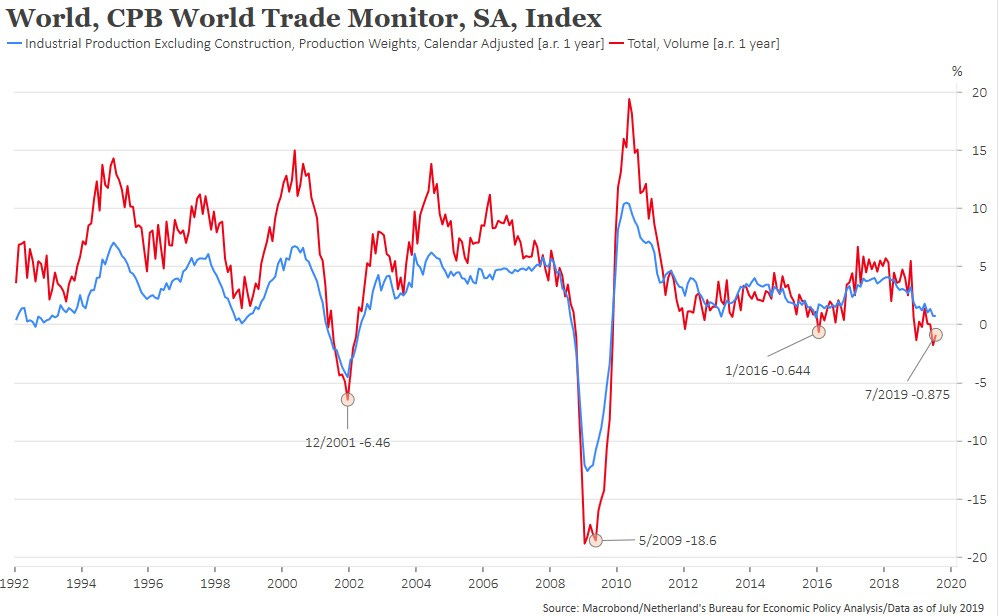

China’s heavy industry state-owned enterprise sector experienced a hard landing in 2014-16 that ended the commodity super cycle and drove a number of emerging market countries into recession. Their export sector is going through a similar contraction that began well before the Trump trade war and is sending Germany into recession. These twin malinvestment busts were inevitable, they were created by policymakers circumventing market forces. The first bust, state-owned heavy industries, was the first crack in socialism with Chinese characteristics. The second economic shock, the export sector, is yet another failure of mercantilism.

China’s economic development has progressed to the point where they cannot feed or power themselves; they are likely to run a current account deficit for decades. We sympathize with those that argue they should lose their emerging nations status at the World Trade Organization, perhaps even be evicted altogether given the state control of their economy and incompatibility with the rules and intent of WTO. Nevertheless, the market is resolving global imbalances and barriers to trade or capital controls that are intended to assist Adam Smith’s invisible hand, might be effective politics, but are risky, at best, policies.

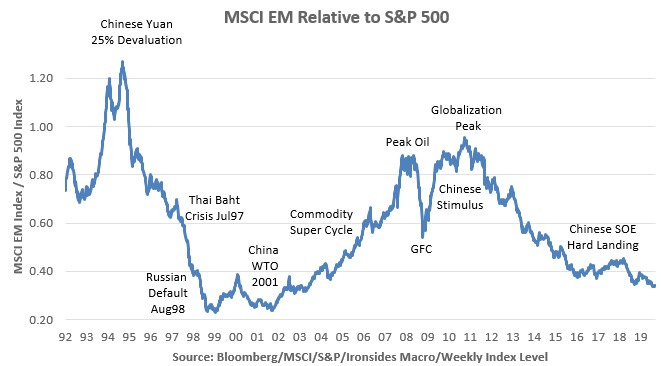

We first turned bearish this cycle on emerging markets and China when we wrote the asset allocation portion of the Barclays 2011 Global Outlook. Our thesis was simple, the spread between emerging and developed world economic growth appeared to have peaked and inflationary pressures in EM were forcing monetary policy tightening, while the developed world central banks were easing. Shortly thereafter, during research we were conducting on the shale energy revolution, came across the US manufacturing renaissance thesis. Our favorite report was from the Boston Consulting Group called “U.S. Manufacturing Nears the Tipping Point”, March 2012.¹

“The United States has been losing factory jobs for so long that many observers have all but written off manufacturing as a meaningful part of America’s economic future. The mass exodus of production following China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) deepened this pessimism.

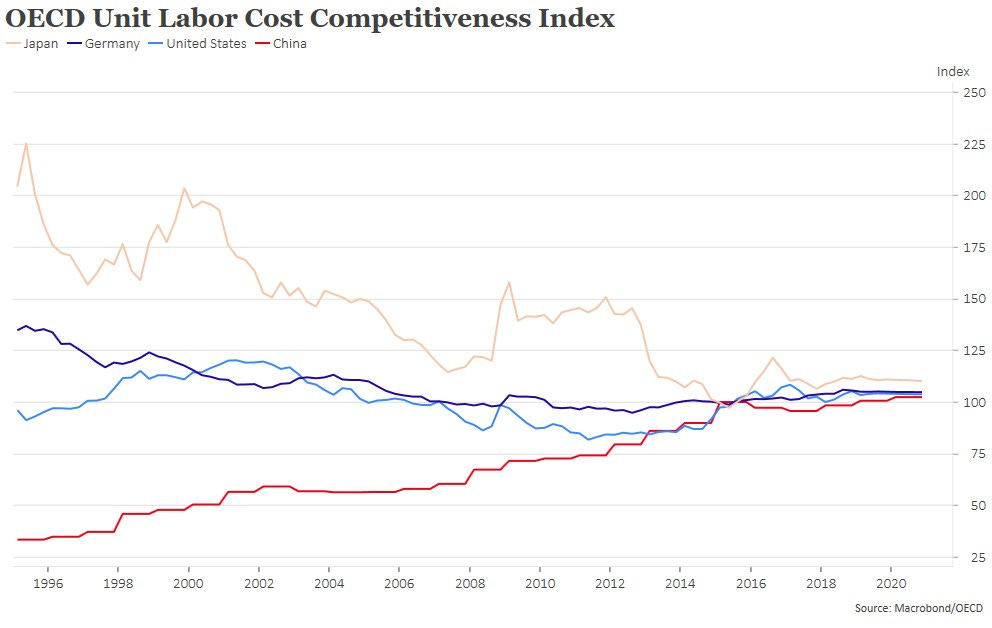

But the tide is starting to turn. In The Boston Consulting Group’s first report in this series (Made in America, Again: Why Manufacturing Will return to the U.S., BCG Focus, August 2011), we explained how rising wages and other forces are steadily eroding China’s once-overwhelming cost advantage as an export platform for North America. By around 2015, we concluded - when higher U.S. worker productivity, supply chain and logistical advantages, and other factors are taken fully into account - it may start to be more economical to manufacture many goods in the U.S. An American manufacturing renaissance could result.”

¹https://www.bcg.com/publications/2012/manufacturing-supply-chain-management-us-manufacturing-nears-the-tipping-point.aspx

Markets were coming to grips with the effects of shale energy; our chemicals analyst at Barclays detailed how US commodity chemical companies went from the high cost to low cost producer virtually overnight. The May 2011 Great East Japan and Earthquake and summer floods in Thailand disrupted supply chains for autos then electronics, for months each. The second ‘Beggar Thy Neighbor’ currency war began as the ECB, BOJ and PBoC targeted a weaker exchange rate as post-crisis demand for manufactured goods left these export dependent - mercantilist - economic systems burdened with excess capacity built for the golden age of globalization. Emerging market equities relative to developed markets, peaked in late 2010 and did not stabilize until early 2016. There still has not been a rebound.

Another colleague, Scott Davis now of Melius Research, who covered multi-industry industrial equities, walked me through the large efficiencies of US manufacturers in China relative to Chinese SOEs, as well the rampant intellectual property theft. The model was shifting, produce in China for consumption in China, not for export to the rest of the world. Later, while at BlackRock, the CEO of MMM told a group of investors that their model was to produce in the country where they sold the products. As BCG forecast, labor cost convergence, higher energy and transportation costs, as well as increased supply chain and exchange rate risks were eroding the benefits of outsourcing. Only the least efficient, highest margin technology sector remain committed to China, but as tech as unit growth slowed for hardware, technology transfer requirements, increased tax rates and implicit costs like IP theft, seem likely to push tech companies to build new capacity outside of China as well.

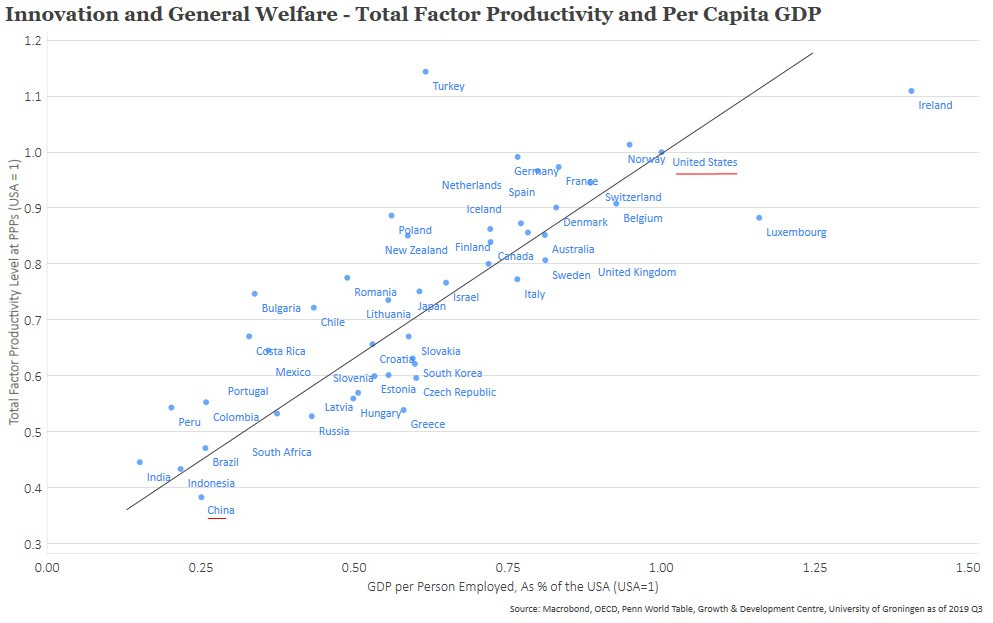

Everything that has unfolded since I first did this research early this decade has been unsurprising. China has had two investment busts. The US manufacturing sector has been adding jobs for the first time in two decades and manufacturing structures investment is slowly turning higher. Perhaps the most compelling chart in this note, is total factor productivity at purchasing power parity, a proxy for innovation, and per capita GDP. Look at the relative positions of the US and China. The often cited ‘threat’ of China’s economy surpassing the US in total size is a strawman. GDP is a measure, and not a particularly helpful one, of aggregate output whether it is steel piling up in the corner or software that makes it possible for you to work from anywhere. Innovation, productivity and GDP per capita drives the standard of living.

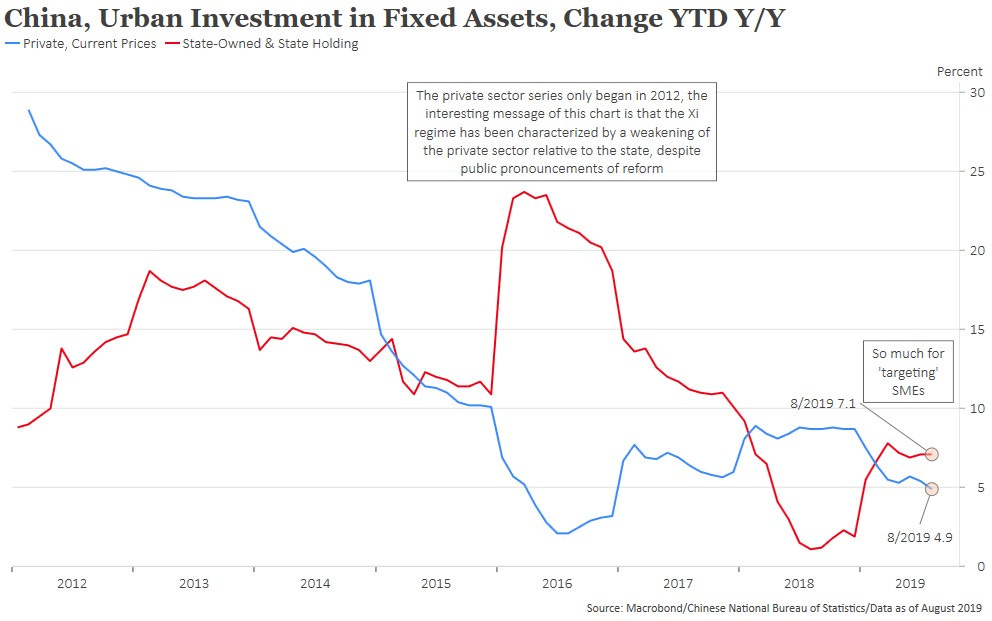

We walked a client through the latest round of Chinese economic releases yesterday. We began with August fixed asset investment at 5.5%, below the forecast of an unchanged level of 5.7%. China’s latest round of stimulus is ‘targeted’ at small and medium private sector enterprises, however, in August state-owned investment increased 7.1% year-on-year, unchanged from July and private sector investment increased 4.9%, down from 5.4% in the previous month. Next we discussed industrial production, which at 4.4% was the weakest report since 2002. Again the composition was as you would expect from a struggling command and control economy, steel production increased 9.3%, electricity output grew 1.7%, auto production fell 0.6% while mobile phones dropped 6.2%. We closed the discussion with Thursday evening’s August industrial profits report. Cumulative 2019, relative to the first 8 months of 2018, profits fell 1.7% while sales grew 4.7% highlighting margin pressure likely attributable to piling steel into warehouses. Sounds like Schumpeter was correct about the tendency for profits to vanish, for command and control economic systems, not market economies.

If you except that the state control of the means of production and mercantilist economic systems have all eventually failed, while these models were important for pulling hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty, China needs to evolve to escape the middle income trap or to repeat the collapse of the Ming Dynasty. This might seem a distant analog, however, in Charles Mann’s fascinating '“1493”, a large portion of the book covers the import of South American silver to China in Spanish galleons that facilitated developing a monetary system that had been chaotic. Export of Chinese textiles that destroyed Spanish producers, and the Chinese destroyed their environment as the population gained wealth but was incapable of feeding the population. The Ming’s fell to the Manchurians in 1644, 79 years after the Manila galleon route was inaugurated. If socialism with Chinese characteristics does not evolve into capitalism with Chinese characteristic, the Mao dynasty will fall as well.

We have attempted to make our case that there is little need to push the Chinese economy over the edge, socialism and mercantilism are deeply flawed economic systems and the evidence is mounting that the inevitable decline is underway. While this logic may resonate with investors, the political calculus is skewed in the opposite direction. Given that Chinese economic momentum is in a secular downtrend, as long as the political class is viewed by the public as ‘doing something’ they are likely to be given credit for the global economic rebalancing. If their policies prove counterproductive, the effects are most second order, consequently any domestic economic fallout can be easily attributed to China not following the established rules of economic liberalism. Hawkish Chinese policy looks like effective politics, despite the mounting evidence that the positive business confidence shock associated with the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act has been completely offset by trade policy.

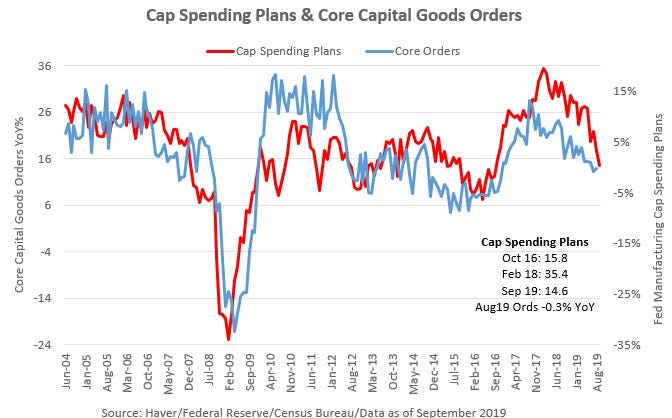

The incoming data started on a favorable note this week, the Markit PMI did not fall below 50 offering some hope that US manufacturing weakness was primarily endogenous due to the early year inventory glut associated with the ‘Echo of ‘87’ transitory negative wealth shock. Housing data also continues to follow the ‘87 analog as the effects of tax reform dissipate and lower mortgage rates boost demand. Still, our regional Fed manufacturing survey capital spending plans index appears to have fallen further in September. Given that our index leads core capital goods orders by 3 months, it is unlikely the weakness we saw in the August durable goods report will recover in 2019. This leads us right into an election year with the statist wing of the Democratic party gaining momentum in the polls and the administration threatening capital controls on Chinese investment on the eve of the next round of formal negotiations. The Tax Cuts & Jobs Act 1H18 capital spending boom is becoming a distant memory.

Measures of Risk

Equity market measures of risk increased this week but are not yet at elevated levels due to low skew and correlation. Treasury vol is above average, currency remains low and credit spreads are near their post-crisis mean.

Barry C. Knapp

Managing Partner

Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC

908-821-7584

https://ironsidesmacro.substack.com

https://www.linkedin.com/in/barry-c-knapp/

@barryknapp

This institutional communication has been prepared by Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC (“Ironsides Macroeconomics”) for your informational purposes only. This material is for illustration and discussion purposes only and are not intended to be, nor should they be construed as financial, legal, tax or investment advice and do not constitute an opinion or recommendation by Ironsides Macroeconomics. You should consult appropriate advisors concerning such matters. This material presents information through the date indicated, is only a guide to the author’s current expectations and is subject to revision by the author, though the author is under no obligation to do so. This material may contain commentary on: broad-based indices; economic, political, or market conditions; particular types of securities; and/or technical analysis concerning the demand and supply for a sector, index or industry based on trading volume and price. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. This material should not be construed as a recommendation, or advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any investment. The information in this report is not intended to provide a basis on which you could make an investment decision on any particular security or its issuer. This material is for sophisticated investors only. This document is intended for the recipient only and is not for distribution to anyone else or to the general public.

Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although such information is believed to be reliable, no representation is made is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of such information. This information may be subject to change without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics undertakes no obligation to maintain or update this material based on subsequent information and events or to provide you with any additional or supplemental information or any update to or correction of the information contained herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates and partners shall not be liable to any person in any way whatsoever for any losses, costs, or claims for your reliance on this material. Nothing herein is, or shall be relied on as, a promise or representation as to future performance. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS.

Opinions expressed in this material may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed, or actions taken, by Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates, or their respective officers, directors, or employees. In addition, any opinions and assumptions expressed herein are made as of the date of this communication and are subject to change and/or withdrawal without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may have positions in financial instruments mentioned, may have acquired such positions at prices no longer available, and may have interests different from or adverse to your interests or inconsistent with the advice herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may advise issuers of financial instruments mentioned. No liability is accepted by Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates or partners for any losses that may arise from any use of the information contained herein.

Any financial instruments mentioned herein are speculative in nature and may involve risk to principal and interest. Any prices or levels shown are either historical or purely indicative. This material does not take into account the particular investment objectives or financial circumstances, objectives or needs of any specific investor, and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, investment products, or other financial products or strategies to particular clients. Securities, investment products, other financial products or strategies discussed herein may not be suitable for all investors. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities, investment products or other financial products mentioned herein.

The material should not be provided to any person in a jurisdiction where its provision or use would be contrary to local laws, rules or regulations. This material is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose absent the written consent of Ironsides Macroeconomics.

© 2019 Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC.