Macro Themes for 2021 & Beyond

Echoes of '60s policy mistakes, Schumpeter's Gale, Capital for Labor, Deglobalization and the End of the 39-Year Bond Bull Market

This is the second for our three-part 2021 outlook series. This is our favorite; it is our attempt to identify macroeconomic themes that will persist through the business cycle. Because we are at the beginning of a new business cycle we are going to start with our expectations for the duration and characteristics of the ‘20s expansion. Last year’s themes were deglobalization, China’s economic model flaws, accelerated technology innovation adoption, a recovery for energy despite ESG mandates and an end to interest rate suppression. The pandemic made the first theme more compelling, exposed and increased the risks of the second, turbo charged the third and delayed, but increased the investment opportunity of the final two.

The ‘20s Expansion, Echoes of the ‘60s Policy Errors

“The years 1961–71 were a part of the Keynesian interlude dominated by a strong belief that government was responsible for stabilizing an unruly private sector. The distinguishing characteristics were two related beliefs: (1) that policymakers could adjust their actions in a timely way to smooth fluctuations, and achieve full employment with high growth and low inflation, and (2) that policymakers could choose and achieve the right, possibly optimal, combination of inflation and full employment. Keynesian economists called their program “the new economics” to signify the departure from prevailing orthodoxies.”

“A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 2, Book 1, 1951-1969”, Allan H. Meltzer

The 1960 presidential election took place amidst a recession that began in April and ended in February 1961. The Kennedy Administration brought the new-Keynesians into the Federal Reserve and throughout the administrative state. While their earliest actions were to accelerate depreciation schedules and later cut tax rates, which contributed to strong investment. The Kennedy and later LBJ administrations tipped the scales of Chairman Martin’s Federal Reserve he described as independent within (not from) the administration, heavily towards the unemployment mandate of the Employment Act of 1946 while they doubled outlays to pay for the Great Society and Vietnam War. The Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors Walter Heller “went to Washington thinking we ought to end the independence of the Federal Reserve”. Inflation came into the ‘60s as a lamb averaging 1.3% for the first half of the decade but went out like a lion at 4.2% for the second half. Earnings growth boomed at 12.4% average annualized for the first half of the business cycle before slowing sharply to 1.7% in the second half of the cycle underscoring the different impact of reflation and inflation on profit margins. The S&P 500 multiple increased throughout the ‘50s to nearly 20 by JFK’s inauguration where it remained throughout what at the time, was the longest business cycle in US history. In short, what began as an optimal investment environment, due to low and stable inflation, accommodative monetary policy and supply-side tax reform, led to the Great Inflation and economically devastating decade of the ‘70s in large part due to policy errors and policymaker hubris.

We do not believe that Janet Yellen or any of President-elect Biden’s economic advisors believe the independence of the Fed should be ended, however, with federal debt at levels last reached during World War II and entitlements created in the ‘60s on the verge of reacceleration, the best the Fed can hope for is to be independent within the administration. Consider the economic school of thought likely to dominate public policy this cycle. The country elected a Democrat in a recession like in 2008, though it did not give his party control over the federal or state and local governments to the same extent. The perception that China, a command-and-control economic system, handled the crisis better than the US market economy is reasonably pervasive. China is tightening control despite clear evidence that their response to the global financial crisis was the greatest fiscal misallocation of resources of all-time. US markets rally on weak data due to the expectation that the probability of stimulus will increase. This naïve market reaction inevitably has a nasty second order effect as it becomes clear that spending multipliers on government outlays are lower than forecast by the IMF and Keynesian consensus and tax hike negative multipliers are greater. Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) will result in scaring, the policy response in the US and the rest of the developed world is likely to be similar to the ‘60s. The case for inflation grows.

There is one final issue to address before we move on, the duration of the expansion. Since the ‘80s, the average duration of an expansion has roughly doubled to 9 years. There are no debt or real investment related imbalances in the private sector that are likely to led to a contraction in the near term. Asset prices are a different story, by all historic measures real interest rates, stock prices and credit spreads are elevated and with monetary policy heavily skewed towards the employment portion of their mandate, financial instability is a near and present danger. Within this context it is worth considering the difference between the tech bubble bursting in 2000 with little associated debt, and debt financed housing bubble. Given that the federal government is the only sector with debt above threshold levels relative to GDP of 90%+, a policy response to that debt, tax hikes or monetary policy tightening were inflation to push interest service costs to levels that crowded out government spending, are possible catalysts for an end to the business cycle. Still, we suspect that like the ‘60s, these pressures will build over time and will not be sufficiently acute to led to a policy mistake that causes the next recession until the second halve of the decade at the earliest. Alas for classic economic liberals and others that believe like Meltzer the private sector is inherently stable, it is policy that creates instability, the Keynesians are in control, for now. Consequently, we expect a favorable environment for real and asset investment in the early years of the ‘20s, later in we expect the effects of Keynesian monetary and fiscal policy to prove costly.

Implementation of this theme: Long inflation beneficiaries; Treasury breakevens or inflation swaps, commodities and related equities

Schumpeter’s Gale: The Pandemic Positive Productivity Shock

For much of the ‘10s, economists debated slower global productivity growth. We spent considerable time researching the topic in the middle of last decade during our investment management sabbatical at BlackRock. Like Robert Solow’s quip in 1987, ‘you can see computers everywhere, except in the productivity numbers’, the power and disruption of mobile computing and weak productivity growth was a paradox. We offer two broad explanations; first the global labor supply shock, a 120% increase from 1990-2010, left most of the world dependent on cheap labor for goods production. As the rate of change of labor supply slowed, a lack of capital investment resulted in slower output. The second factor was detailed in an excellent book on the topic, “A Great Leap Forward, 1930s Depression and US Economic Growth”, Alexander Field. The theme of the book is productivity improvements from ‘20s innovation were obscured by the financial crisis in the ‘30s. After WWII, productivity boomed in part because the Depression accelerated creative destruction. The war put the boom on hold for 5 years.

Prior to the pandemic evidence was building that as the labor market tightened, service sector businesses were increasingly substituting capital for labor and adopting technology innovation. Productivity growth increased in 2018 and 2019, despite a negative contribution from the manufacturing sector as the trade war sent global goods production and trade into recession. Easy to conceptualize examples include Starbucks investment in their mobile app and preordering that solved their assembly line bottleneck and Newark Airport’s Terminal C where iPads replaced humans for food and beverage service. The pandemic was a positive productivity shock that accelerated adoption of technology to deliver goods and services.

We doubt there will be much resistance to this thesis, there are however two important related questions. The first is whether the three deadweight sectors detailed in a 2016 Gallup analysis of productivity, housing, education and healthcare received a shock sufficiently large from the pandemic so that inflation in these sectors falls relative to the general price level and outcomes begin to improve. We have confidence this will occur in housing and healthcare. Healthcare deliverers face an existential threat from the progressive wing of the Democratic Party and have been forced to integrate technology in basic wellness as well as advanced treatment by the pandemic. The work-from-home necessity appears to have increase the mobility of the workforce and crowding into cities or regions thereby reducing the productivity drag we suffered during 30 years of NYC commuting. Education has been a major disappointment during the pandemic, teachers’ unions resisted compelling scientific evidence and held politicians hostage. However, while the Democrats are taking over the federal bureaucracy, they lost ground at the state and local level to the Republicans who were already in the majority. Student loan forgiveness and associated moral hazard threatens to exacerbate the borrowing and cost spiral at the university level. However, competition for public schools from charters seems likely to increase further and the integration of technology as a supplement to traditional in-person learning seems likely to return power to professors and teachers from administrators and unions and slow the cost spiral. Our approach to capitalizing on a turnaround in these deadweight sectors is our healthcare overweight. After three decades of margin contraction, we expect technology integration to reverse that trend. Healthcare is the largest contributor to S&P 500 revenues, however peak margins in 2Q19 were 6.5%, far below the 20.8% peak for the technology sector.

Implementation of this theme: Reduce Technology and Communication Services exposure, increase healthcare, industrials, financials and consumer exposure as the benefits of digitization migrate from the producers to users.

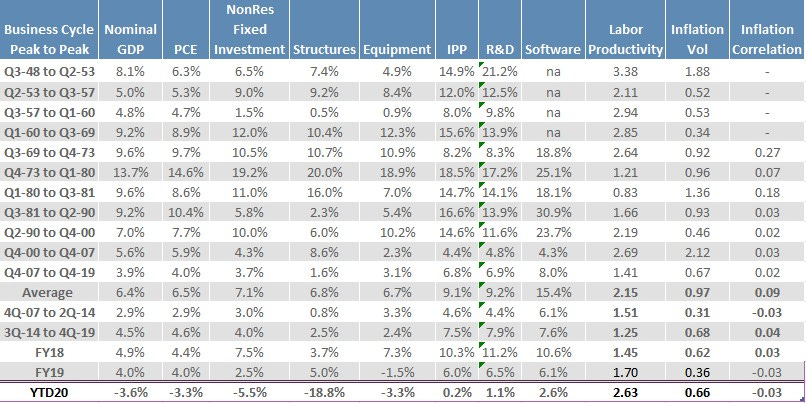

Rebuilding the US Capital Stock

The two strongest decades for nonresidential fixed investment (NFRI) were the ‘60s and the ‘90s. In both cases real investment grew at twice the post-WWII average of 4.5% following significant supply-side tax reform. In the first case, tax reform began early in the cycle, in the second tax reform was enacted late in the previous cycle as is currently the case. Both cycles began with relatively low and stable inflation expectations. The Georgia Senate runoff elections could degrade the outlook somewhat, though the economic case for stronger capex was in place prior to the passage of the Tax Cuts & Jobs Act. The balance of this section is a reprint with some minor modifications from last week’s 2021 Outlook. Please skip ahead if you read last week’s note.

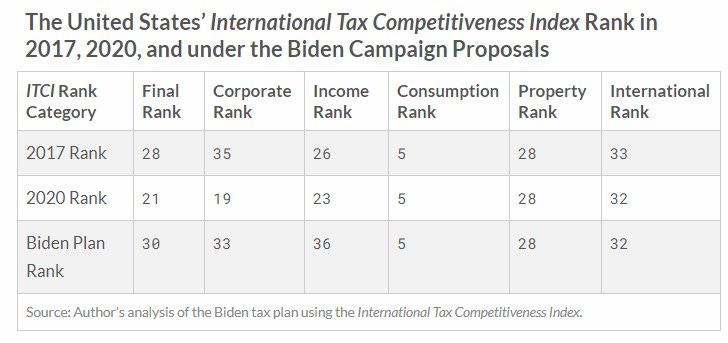

A 2017, pre-Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA), Congressional Budget Office International Comparison of Corporate Tax Income Tax Rates and analysis from Robert Barro and Jason Furman from Harvard titled Macroeconomic Effects of the 2017 Tax Reform, reach the conclusion that keeping TCJA’s 21% rate will significantly reduce the after-tax cost of structures investment integral to the evolution to ‘just-in-case’ supply chain management. The factor not explored in these reports that will have a larger immediate effect, is a rebound in business confidence from the trade war, pandemic and presidential election year uncertainty.

Capital investment was weak through much of the ‘10s, like the ‘50s prior to the Kennedy Administration supply-side tax reform that led to the first post-WWII capex boom. Additionally, the economics of manufacturing in China to import to the US were largely gone by the mid-’10s ( U.S. Manufacturing Nears the Tipping Point) and supply chain risks, after a series of shocks beginning with the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011, including the trade war, can no longer be ignored following the pandemic. One final point, demographics are destiny and the developed world has fully exploited the 120% increase in the global supply of labor from 1990-2010 (Demographics Will Reverse Three Multi-Decade Global Trends), consequently, substitution of capital for labor is likely to be a major theme in the ‘20s. This implies margin expansion broadening from the technology and communication services to consumer, healthcare, industrials and financial sectors. It also implies the trend change in productivity growth from 1% to 1.7% in 2019 attributable to the service sector, was not an aberration and will likely strengthen further as the benefits of digitization diffuse across sectors.

The pandemic was a positive productivity shock.

Implementation of this theme: Long industrials particularly those that are at the forefront of the industrial internet.

Deglobalization, Collectivism and Mercantilism

Calling for the end of history for Mercantilism is analogous to predicting the end of collectivism, these ideas never really die, they are on a pendulum though not the same one. The collectivism pendulum is swinging towards command and control systems in most of the world including the US, though not as quickly as political strategists expected given the strong performance of the GOP everywhere except the top of the ticket. On the other hand, Mercantilism peaked in the ‘00s and the pendulum began swinging towards deglobalization in the ‘10s. In the world’s number two economy, a hard shift towards increased command-and-control combined with deglobalization seems likely to make this a difficult decade. The ‘20s expansion is beginning with an exceptionally robust recovery of global trade as a consequence of the twin shocks of the trade war and pandemic, the last cycle began similarly only to see Asian trade growth slow to a third of the 2000’s rate. By the early ‘10s, the most efficient manufacturing companies in China, US multi-line industrials, concluded that the increased labor, transportation and energy costs no longer covered the implicit costs from intellectual property theft, exchange rate and supply chain risks. Most adopted what Honeywell calls a ‘locally sourced’ model, manufacture where final demand resides. Only the high margin technology sector is holding out, we expect that sector to adopt the industrials model this cycle.

There is plenty of good analysis of Chinese economic activity that offers better information content than the flawed official data. Nonetheless, even the mix of the official data leads to the unequivocal conclusion that like the heavy industry hard landing of 2014-2016, the response to the pandemic from the central committee and General Secretary Xi was to deepen state control over the means of resources. Fixed asset investment recovered more quickly for state-owned-enterprises than private entities, the rebound in industrial production was led by heavy industry, retail sales lagged production and the recovery in exports is well ahead of ordinary imports (domestic demand). Admirers in the west marvel in China’s handling of the pandemic, students of economic history are increasingly confident China’s fatal conceit is increasingly likely to doom them to the middle-income trap. This theme runs deeper than China. European fiscal integration and the BOJ’s position as the largest stockholder in Japan are moving these countries towards greater state control over the means of production, a form of corporatism. We see few signs that these export dependent economies are well positioned for another decade of deglobalization.

Implementation of this theme: Underweight Chinese equities particularly State-Owned-Enterprises (banks and heavy industry), and developed world export-dependent markets (Germany, Japan, South Korea).

The End of the 39-Year Bond Bull Market

There are three major variables in our forecast for higher bond yields in the coming cycle. The first is our inflation forecast we discussed in last week’s note. The second can be characterized as demographics are destiny. Goodhart and Pradhan’s capital for labor thesis is likely to begin in the US, and in fact already has, though in part due the negative shock to business confidence from the trade war and pandemic, increased demand for capital has been concentrated in intellectual property products that are financed by equity rather than debt capital. In the ‘20s as supply chains are restructured demand for capital to build physical plant financed by debt is likely to increase significantly. The additional demographic shift in demand for capital is the largest age cohort, Millennials, moving into the peak life-style consumption stage. A key variable in research explaining the 39-year bond bull market is the aging of the developed world population and in the US, it was Boomers leaving peak consumption years and the associated demand for savings and fixed income. That process is now shifting as the Boomer influence is overwhelmed by Millennials.

The final factor in our bearish bond forecast is deglobalization. During the peak following China’s entry into the WTO and reduced tariffs in the mid ‘00s, one of our first calls every morning was to Lehman’s Treasury desk to see how large the overnight demand from China was. Japan spent ~$350 billion attempting to weaken the yen from October 2003 through March 2004, 5 & 10-year yields rallied over 1% in the ensuing 2 months beginning the day after the last BOJ dollar purchases. Until 2005, China’s currency regime was a hard peg, it is still controlled. Petrodollar recycling was another source of demand for US fixed income assets due to currency pegs, that demand collapsed in 2015 as oil exporter revenues dropped $600bn+ as the shale revolution triggered a 75% drop in the price of crude. We did extensive analysis of energy’s contribution to the current account deficit beginning in the ‘60s and ran statistical causality analysis that supported our view that periods of high oil prices and large US energy trade deficits led to secular weakness in the dollar (‘70s and ‘00s), and the strong dollar decades (‘80s until the Plaza Accord, ‘90s and ‘10s) were partially a consequence of a falling energy trade deficit. Despite the current struggles in the shale sector, we do not believe large energy trade deficits are likely to return in the ‘20s. Consequently, Petrodollar and Asian goods export related demand for US fixed income is likely to be far smaller in the ‘20s than the ‘10s and the peak in the ‘00s.

This leaves the goods trade deficit as the primary source of the US current account deficit. There is no doubt that the Mercantilists will not go quietly into the night, they will make every attempt to weaken their currency to support their export dependent economies and the US remains an attractive destination for capital (the opposite side of the current account ledger). Nonetheless, monetary policy is even more inefficacious and even counterproductive in the rest of the large economies relative to the US. The economic and risk management forces of deglobalization imply a shrinking of the US goods deficit through the cycle. Additionally, the US services surplus is likely to widen further, particularly in financial services with tighter regulatory policy under the Biden Administration due to financial sector innovation. On balance, with a 3-decade disinflationary trend ending, higher domestic demand for capital and lower foreign demand for dollar denominated assets, only the Federal Reserve and Treasury stand in the way of higher rates. Financial repression will slow but is unlikely to stop a secular trend toward higher rates. One final point, markets generally have sneak previews of major inflection points. In the case of higher rates, the 10-day shock to risk parity in March when Treasuries failed as a risk mitigation tool for equities and collapsed concurrently was a warning sign that policy cannot completely mitigate risk.

Implementation of this theme: The death of the 60/40 optimal portfolio and risk parity goes the way of portfolio insurance.

Barry C. Knapp

Managing Partner

Director of Research

Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC

908-821-7584

bcknapp@ironsidesmacro.com

https://ironsidesmacro.substack.com

https://www.linkedin.com/in/barry-c-knapp/

@barryknapp

This institutional communication has been prepared by Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC (“Ironsides Macroeconomics”) for your informational purposes only. This material is for illustration and discussion purposes only and are not intended to be, nor should they be construed as financial, legal, tax or investment advice and do not constitute an opinion or recommendation by Ironsides Macroeconomics. You should consult appropriate advisors concerning such matters. This material presents information through the date indicated, is only a guide to the author’s current expectations and is subject to revision by the author, though the author is under no obligation to do so. This material may contain commentary on: broad-based indices; economic, political, or market conditions; particular types of securities; and/or technical analysis concerning the demand and supply for a sector, index or industry based on trading volume and price. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. This material should not be construed as a recommendation, or advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any investment. The information in this report is not intended to provide a basis on which you could make an investment decision on any particular security or its issuer. This material is for sophisticated investors only. This document is intended for the recipient only and is not for distribution to anyone else or to the general public.Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although such information is believed to be reliable, no representation is made is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of such information. This information may be subject to change without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics undertakes no obligation to maintain or update this material based on subsequent information and events or to provide you with any additional or supplemental information or any update to or correction of the information contained herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates and partners shall not be liable to any person in any way whatsoever for any losses, costs, or claims for your reliance on this material. Nothing herein is, or shall be relied on as, a promise or representation as to future performance. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS.Opinions expressed in this material may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed, or actions taken, by Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates, or their respective officers, directors, or employees. In addition, any opinions and assumptions expressed herein are made as of the date of this communication and are subject to change and/or withdrawal without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may have positions in financial instruments mentioned, may have acquired such positions at prices no longer available, and may have interests different from or adverse to your interests or inconsistent with the advice herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may advise issuers of financial instruments mentioned. No liability is accepted by Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates or partners for any losses that may arise from any use of the information contained herein.Any financial instruments mentioned herein are speculative in nature and may involve risk to principal and interest. Any prices or levels shown are either historical or purely indicative. This material does not take into account the particular investment objectives or financial circumstances, objectives or needs of any specific investor, and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, investment products, or other financial products or strategies to particular clients. Securities, investment products, other financial products or strategies discussed herein may not be suitable for all investors. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities, investment products or other financial products mentioned herein.The material should not be provided to any person in a jurisdiction where its provision or use would be contrary to local laws, rules or regulations. This material is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose absent the written consent of Ironsides Macroeconomics.© 2020 Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC.