This is the first of three outlook notes; this week’s note will address the economic, policy and market outlook for 2021. Next week’s note will cover macro themes we expect to persist through 2021 and beyond. The final note, to be released on the last Saturday before Christmas, will be our 2020 in review note.

Three Tailwinds and Looming Policy Risks

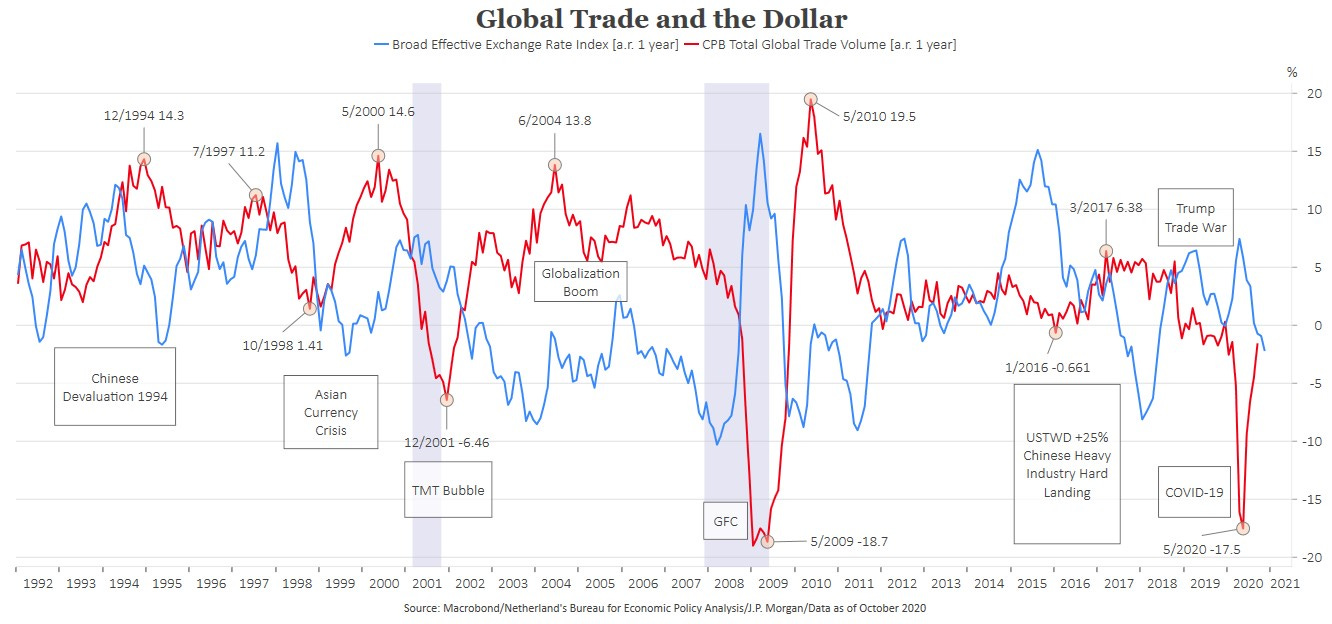

We expect double-digit US equity market returns in 2021 and negative returns for high quality, long duration fixed income primarily attributable to a faster than expected closing of the output gap resulting from both the pandemic and the trade war-induced global manufacturing recession that preceded Covid-19. The first tailwind is the combination of the trade war related global trade and manufacturing recession and the pandemic induced supply chain disruptions, as well as consumption mix-shift from services to goods. A robust recovery in global trade runs counter to the secular trend of deglobalization, in essence 2021 is likely to be the last hurrah for export-dependent nations as the world shifts from ‘just-in-time’ to ‘just-in-case’ supply chain management. The recent strong relative performance of German, Japanese and export-dependent emerging market equities is attributable to the rebound in global trade. We expect these markets to lose relative strength momentum prior to export growth peaking, however, for the first part of 2021 the ‘Mercantilists’ are likely to outperform. The recovery in emerging market equities should prove more durable than export-dependent developed markets due to continued relative wage-cost advantages for labor-intensive products and the lagged effect of dollar weakness. The mid-2014 to 2016 25% increase in the trade-weighted US dollar had a counterintuitive effect on global trade best illustrated by Mexican exports to the US. Despite an increase in trend personal consumption growth from 1.9% for the first 5 years of the US expansion to 3.0%, Mexican exports weakened due to a tightening of the supply of trade finance. This effect more than offset the classic currency competitiveness effect (cheaper goods boosting demand, link to BIS research).

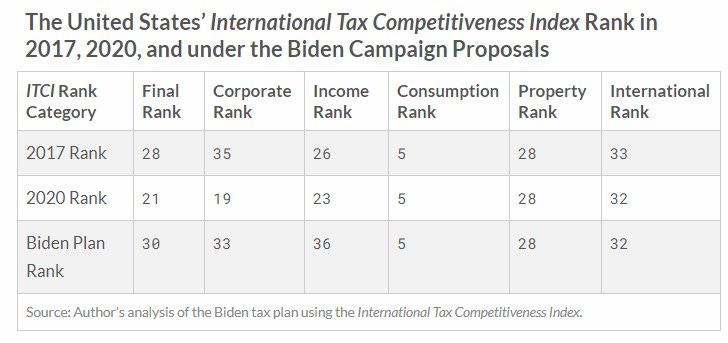

The second tailwind, a capital investment recovery in 2021, will have a more significant and persistent impact on the US equity market and economy than the first, but has a hurdle to overcome in Georgia on January 5th. A 2017, pre-Tax Cuts & Jobs Act (TCJA), Congressional Budget Office International Comparison of Corporate Tax Income Tax Rates and analysis from Robert Barro and Jason Furman from Harvard titled Macroeconomic Effects of the 2017 Tax Reform, reach the conclusion that keeping TCJA’s 21% rate will significantly reduce the after-tax cost of structures investment integral to the evolution to ‘just-in-case’ supply chain management. The factor not explored in these reports that will have a larger immediate effect, is a rebound in business confidence from the trade war, pandemic and presidential election year uncertainty.

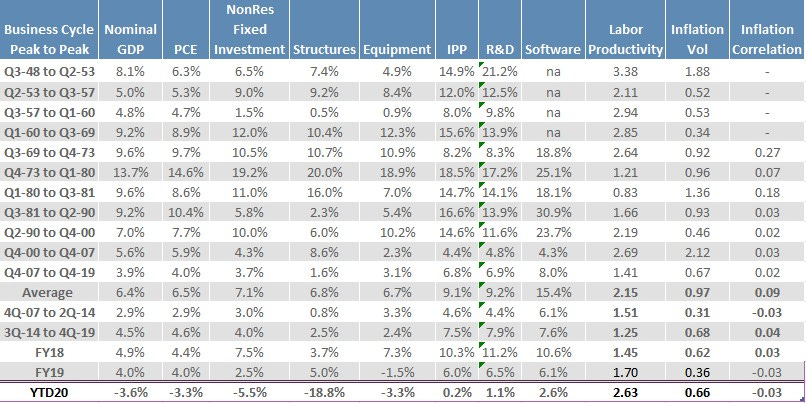

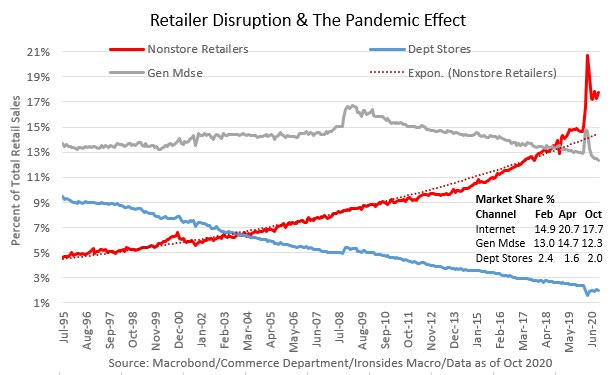

Like the Tax Reform Act of 1986, TCJA was passed late in the business cycle and while capital investment strengthened in the late ‘80s, the tax incentives were offset by tighter monetary policy, disruption in the housing market and a stock market crash that weakened business confidence. The real effects of the ‘86 tax reform developed during the following business cycle in the ‘90s, when nonresidential fixed investment grew at the fastest rate of any post-war cycle at (real) 9.8% annualized. Capital investment was weak through much of the ‘10s, like the ‘50s prior to the 1964 supply-side tax reform that led to the first post-WWII capex boom, consequently, there is strong precedent for a boom in the ‘20s. Additionally, the economics of manufacturing in China to import to the US were largely gone by the mid-’10s ( U.S. Manufacturing Nears the Tipping Point) and supply chain risks, after a series of shocks beginning with the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011, including the trade war, can no longer be ignored following the pandemic. One final point, demographics are destiny and the developed world has fully exploited the 120% increase in the global supply of labor from 1990-2010 (Demographics Will Reverse Three Multi-Decade Global Trends), consequently, substitution of capital for labor is likely to be a major theme in the ‘20s. This implies margin expansion broadening from the technology and communication services to consumer, healthcare, industrials and financial sectors. It also implies the trend change in productivity growth from 1% to 1.7% in 2019 attributable to the service sector, was not an aberration and will likely strengthen further as the benefits of digitization diffuse across sectors.

The pandemic was a positive productivity shock.

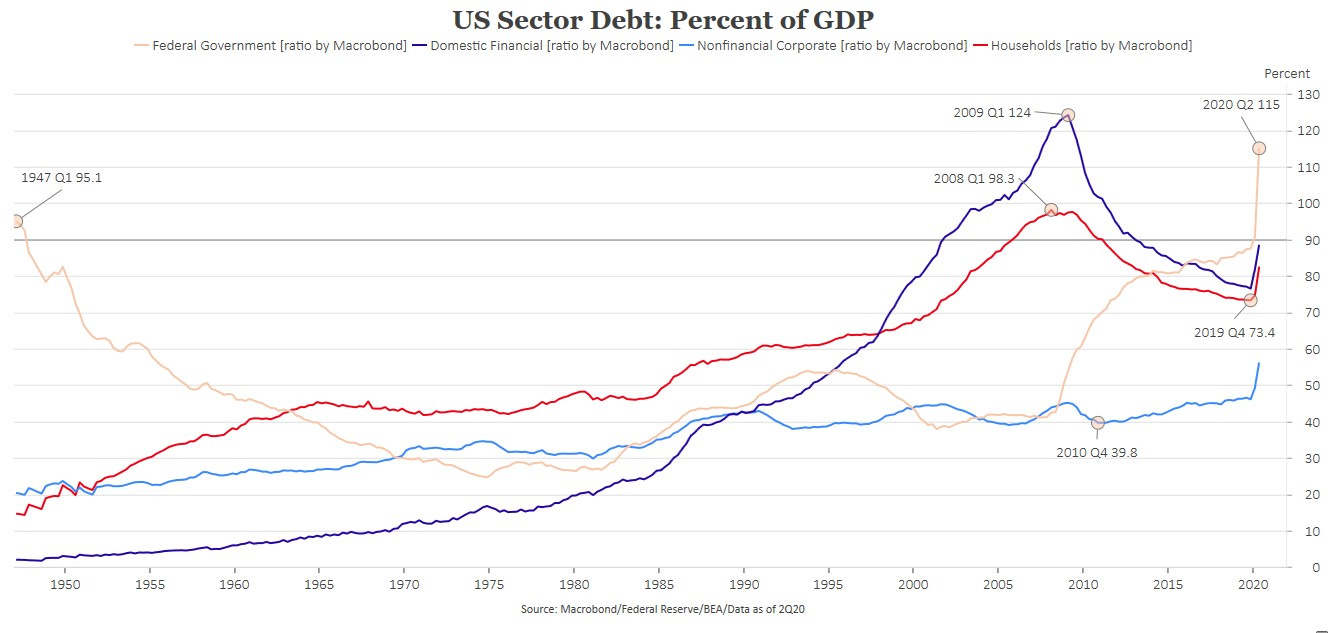

The third tailwind for risky assets generally and economically sensitive cyclical stocks, is reflation. There is both a compelling monetary case for a cyclical increase in inflation and a strong secular argument emanating from global supply chain restructuring. The monetary case is best illustrated by the changes in debt to GDP ratios since the financial crisis. In 2007, household and financial sector debt had never been higher, while government debt was towards the low end of its long-term range. As a consequence, when the monetary base increased dramatically due to Federal Reserve large-scale asset purchases (QE), the velocity of money collapsed. This was because of constraints on supply, both reduced financial sector risk tolerance and the sharpest tightening of regulatory policy since the Great Depression, as well as a collapse in demand as the household balance sheets were devastated by the financial crisis. At the 2010 Kansas City Fed Jackson Hole symposium Carmen and Vincent Reinhart presented an abbreviated version of “It’s Different This Time” titled After the Fall where they analyzed 15 severe post-WWII financial crises. The most persistent economic effect was a decade of disinflation even in cases including currency devaluations. The pandemic was not a financial crisis, household and financial sector debt is low, household financial obligations ratios have never been lower since the Fed began tracking them in 1980 and the debt now resides primarily with the federal government at a level that points squarely at financial repression/debt monetization.

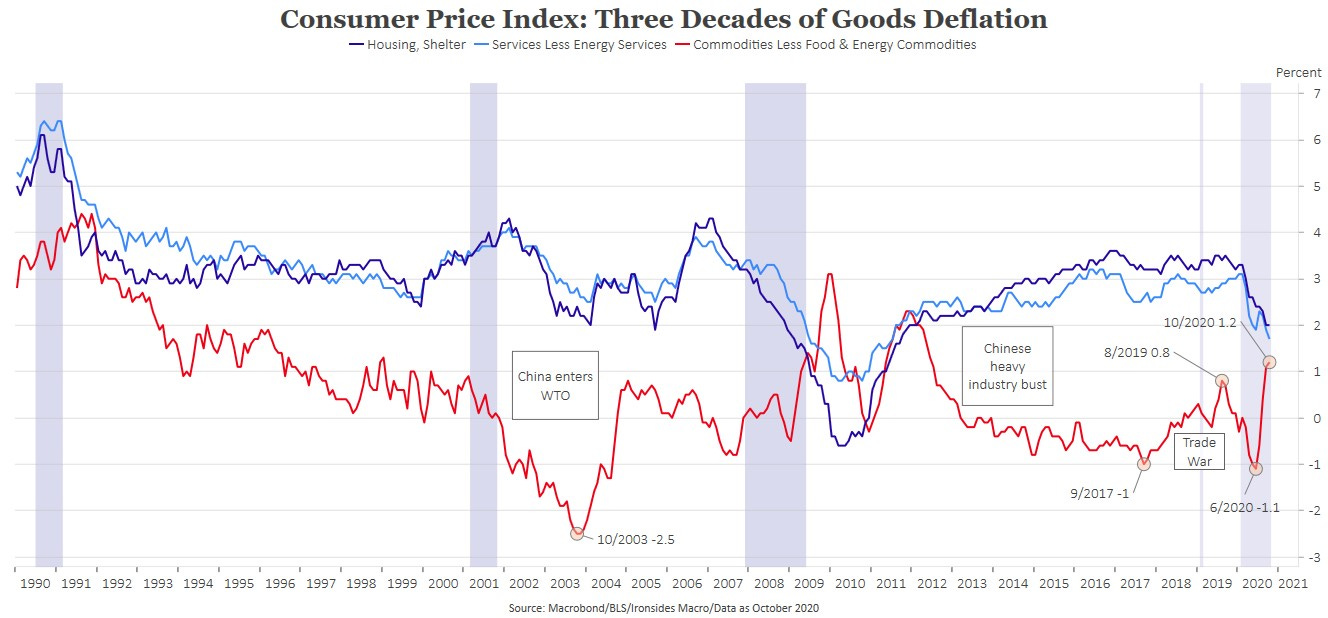

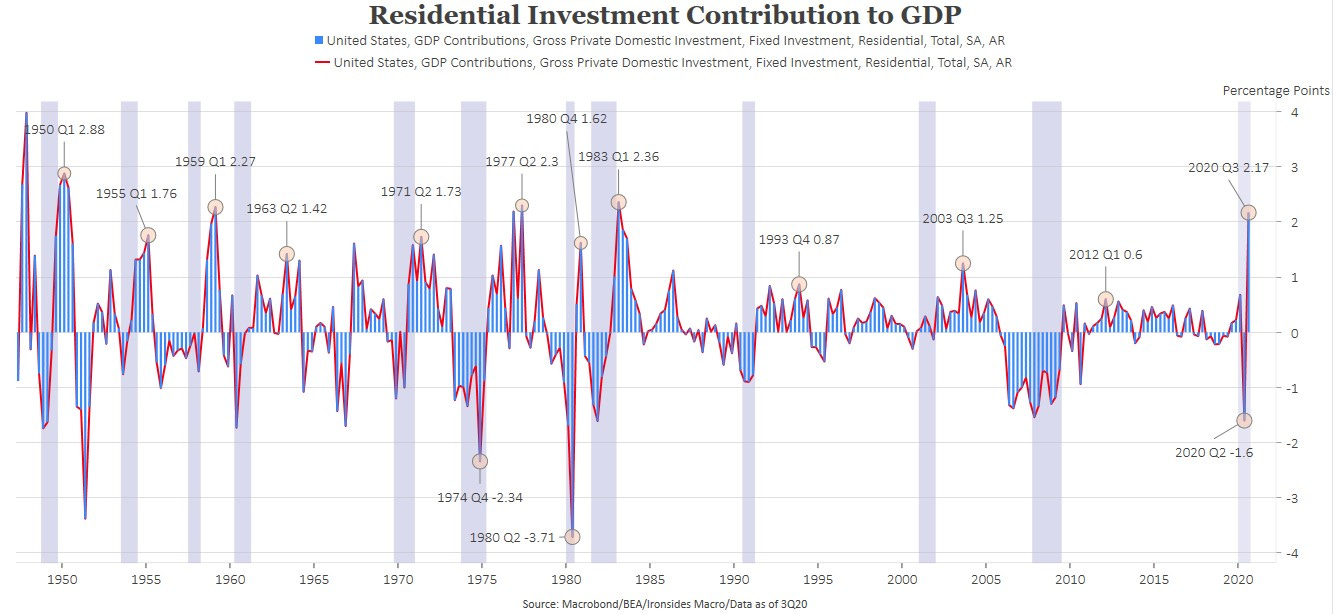

The secular argument for inflation relates directly to the primary source of disinflation for the last three decades, goods prices. The same labor supply shock that we discussed in our discussion of the capital investment outlook is the primary factor in 3 decades of imported goods deflation. The impact of the pandemic on services and non-pharmaceutical interventions in housing (rent moratoriums and mortgage deferrals) have depressed services inflation, however those are likely to rebound sharply in 2021. Additionally, we expect higher and more stable energy prices in the ‘20s due to the trade war and pandemic related conventional oil supply destruction and increased elasticity of supply attributable to shale technology. Consequently, goods price deflation is unlikely in the ‘20s, energy prices will be higher and more stable, housing prices will rise due to the demographic tailwind of the Millennial household formations and services inflation will recover. Technology innovation and related productivity gains in the deadweight sectors of healthcare, housing and education should preclude a late ‘60s/’70s Great Inflation anytime soon, however it seems likely four decade trend of disinflation is ending along with the 39 year bond bull market.

The pandemic was an inflationary shock, while the financial crisis was a deflationary shock.

Economic Outlook: Creative Destruction

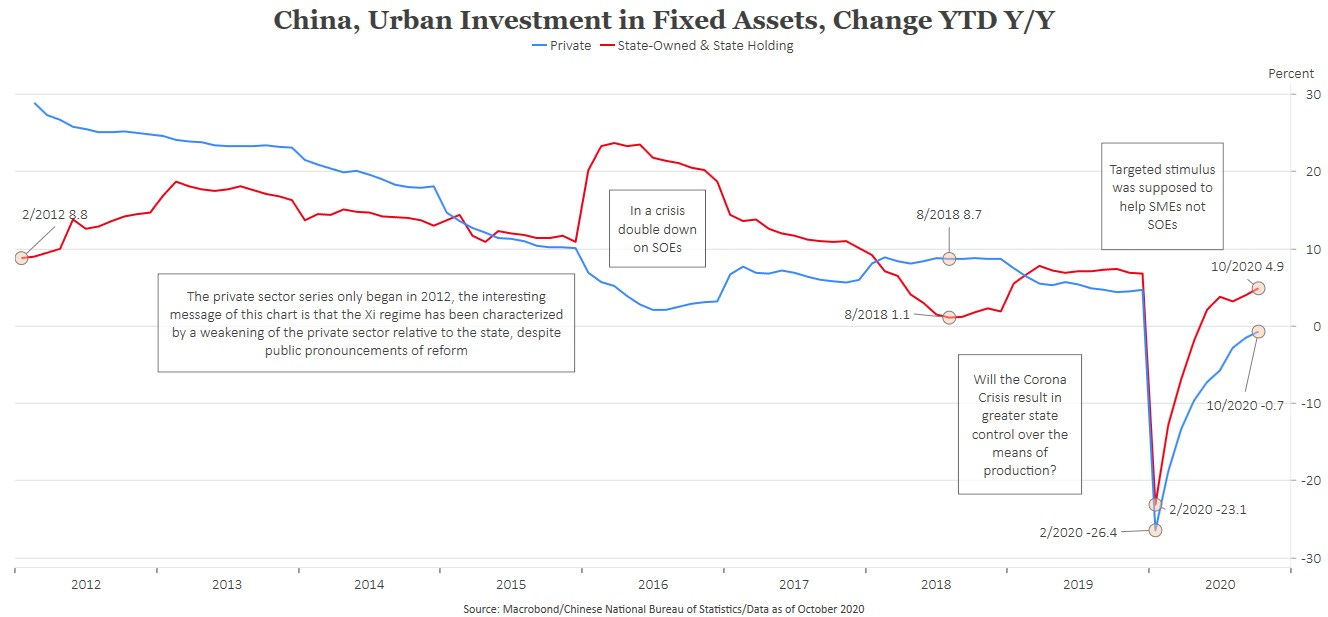

As forecasts for soft and perhaps even negative 1Q21 growth accumulate, we suggest investors realize all growth is not created equal. Tactically, the reduction of expectations will likely contribute to positive economic surprise in the early part of 2021. From a global perspective this means any economist, strategist or investor prognostications that China will be the largest contributor to global growth should be viewed with extreme skepticism. As it stands, China’s ordinary import growth is lagging exports, the recovery in fixed asset investment is being driven by state owned enterprises and retail sales are lagging heavy industry industrial production. This is a plus for commodity investors but is not a reason to buy Chinese equities or to believe they are not headed down the same path as the vast majority of Mercantilists in history. China will benefit from the recovery in global trade, however their policy response and dependence on the export channel will further impair the rebalancing necessary to avoid the middle income trap. Chinese policy is the most extreme example of impairing creative destruction.

In the US, there are two contributors to growth that arithmetically appear small in the national accounts GDP data but have very high multiplier effects: nonresidential capital and residential investment. We are very bullish on both through 2021 and beyond.

Although the November employment report disappointed due because of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), the faster recovery of small businesses and record small business creation during the pandemic, underscores the dynamism, resiliency and creativity of the US economy. It appears unlikely that counterproductive labor stabilization policies will linger as long as they did following the global financial crisis due to a political coalition government rather than the one-party rule from 2009-2010. Given our outlook on capital investment, we expect real wage growth to resume the strong trend that began following the passage of TCJA in 2021. The political structure should also mitigate the suppression of creative destruction that occurred in the ‘10s, there is already evidence that ‘Schumpeter’s Gale’ is accelerating trends that were gaining momentum in the ‘10s in the consumer sector. Still, a Democratic administration, advised by new-Keynesians that believe the private sector is inherently unstable requiring constant public sector intervention, will undoubtedly misallocate resources.

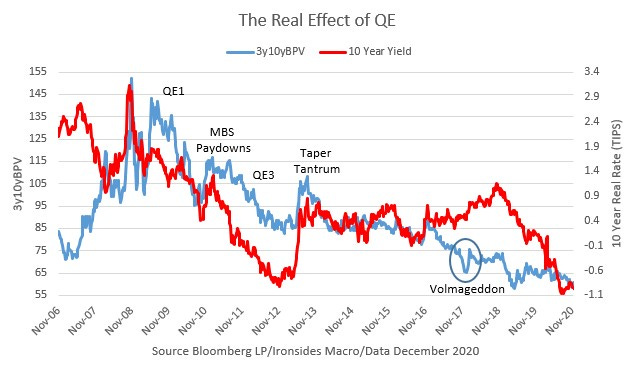

Policy Outlook: This was not a financial crisis

We identified a single monetary policy normalization equity market correction in each business cycle since WWII, except the ‘09 to ‘19 expansion where there were eight. These corrections generally last 6 weeks resulting in an 8-10% equity market pullback. They occur when the Fed gains sufficient confidence in the durability of the recovery and take the initial steps to normalize policy. The first of last cycle’s monetary policy shocks occurred when QE1 was approaching its expiration date of June 2010, the most memorable aspect was the flash crash. We expect most outlook notes to assume policy will remain accommodative throughout 2021 and while we expect the Fed to welcome a continuation of the rally in market implied inflation (breakevens) for at least another 50bp, this does not preclude a monetary policy shock. One possibility is a mix shift from agency mortgage-backed securities to Treasuries due to liquidity impairment concerns that could led to an increase in bond volatility. We do not believe the stock of Fed long-duration assets will shrink anytime soon, but the flow and mix matters. Consequently, even pushback from regional bank presidents concerned about inflation and/or financial instability could led to a monetary policy shock given the current lofty valuations of equities, credit and the weaker dollar related trades including commodities, crypto, and gold. This scenario is unlikely until 2Q at the earliest.

Early in 2010, the recovery was looking symmetric to the recession, until the 111th Congress, without a single Republican vote, passed two massive expansions of the administrative state that restructured the healthcare and financial sectors. Business confidence plunged, and the recovery in capital investment stalled. The Georgia senate elections loom large in avoiding a similar scenario though were the Democrats to pull off a shock sweep in Georgia they would be far short of a filibuster proof majority in the Senate. Additionally, having met Senate Majority Leader McConnell and observed his and President-elect Biden’s central roles in negotiating an end to the debt ceiling and budget battles in 2011, we do not expect any similarly disruptive legislation before the Democrats lose their House majority in 2022. We are less sanguine on regulatory policy given the expansion of the administrative state in recent decades and the interventionist bias of Biden’s economic and policy advisors. Financial sector policy will tighten marginally, though this will primarily serve to expand the nonbank sector. Energy policy will tighten for fossil fuels which will likely raise prices, government subsidies for renewables will misallocate capital and make the sector less investable. Increased labor market interventions could impair dynamism and reduce worker reallocation. These are concerns for late 2021 at the earliest.

Markets Outlook: Transitioning from the early cycle playbook

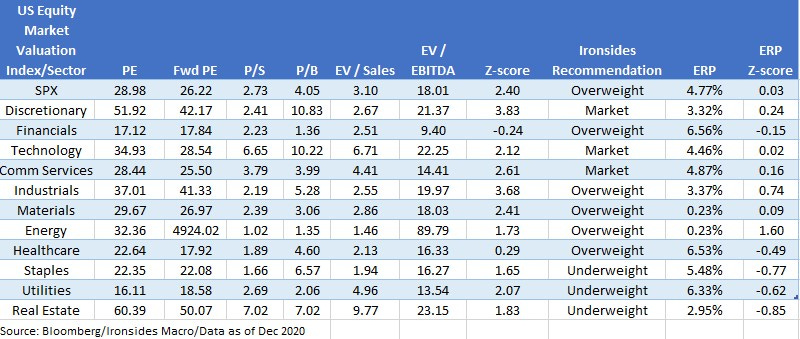

Although the NBER recession dating committee has not yet declared the end of the recession, growth resumed in June and from an investor perspective the ‘20s expansion cycle began on March 23rd. In part because this was likely to be the shortest recession in US history, we have tried to be aggressive with respect to the sector recovery playbook. For example, we swapped out of consumer discretionary into industrials this summer, a transition that took a year for us to make the prior cycle. With the exception of financials, this cycle has followed the recovery playbook. Consumer discretionary, materials, technology and small caps outperformed early, defensives have consistently lagged. We do expect secular trends to become increasingly clear as 2021 unfolds, one of the most prominent is our thesis that the benefits of digitization will migrate to consumers of technology from the producers. Cloud investment growth will continue to grow rapidly, however expensive valuations will make those producers share prices vulnerable to signs the rate of change is slowing, cost are rising, or competition is pressuring margins. Industrials, healthcare, consumer and financial companies will capitalize on digitization and technology innovation adoption will diffuse through these sectors, leading to margin expansion while technology and communication service sector margins are unlikely to expand further and will eventually compress. We think it is time to increase exposure to energy, it has become a tiny fraction of benchmark indices. Consequently, moving to an overweight is hardly heroic, but we suggest allocating 5-10% of your equity exposure to the sector as return on invested capital stabilizes due to greater elasticity of supply from shale technology, the sector matures and demand recovers.

We went on the record in August calling the end to the 39-year bond bull market and everything that has occurred since strengthened our conviction in this outlook. Our inflation outlook and secular trend of capital for labor substitution as the export dependent world ages while Millennials move into the peak consumption stage of the life cycle are key factors in our bearish bond outlook. Federal Reserve and Treasury financial repression will act as a brake on a rapid increase in rates, however implicit in financial repression tactics is an increase in inflation. The failure of risk parity strategies in early March was a warning shot that the 60/40 stock bond model is likely to come under greater pressure, just as there were numerous warning signs of the financial crisis including the auto basis shock in the spring of ‘05 or Quant Meltdown of August ‘07.

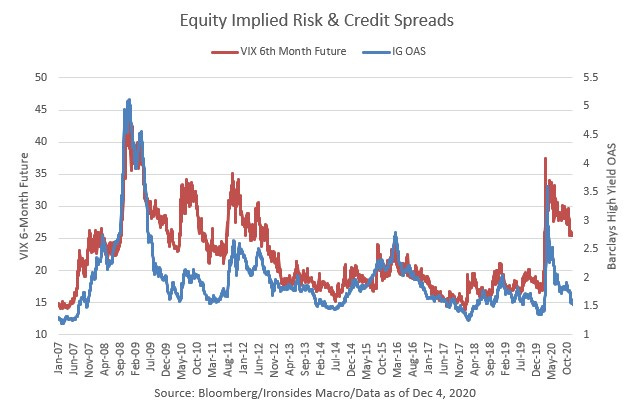

The most persistent effect of Federal Reserve large-scale asset purchases is volatility suppression because of their stock and flow of agency mortgage-backed securities without hedging mortgage prepayment risk. Because the Fed went one step further during the pandemic and purchased credit, this left equities as the only major asset class as an escape valve for volatility. Consequently, given the close relationship between corporate equity and credit, the spread between equity volatility and credit spreads is unlikely to persist. During the first part of 2021, we expect convergence primarily due to lower equity volatility. Perhaps a couple of months into the year, positions with convexity to higher rates and marginal spread widening on investment grade and high yield credit will become attractive.

The mitigation of a series of knowable risks in recent months has led to a drop in demand for dollar denominated ‘safe assets’ and a broad-based move lower for the dollar. Declines in the dollar invariably spark dollar crisis and end to reserve currency forecasts. We are not of this view. We do however believe the decline could be a feature of 2021 following a sharp countertrend move early in the year due to offsides positioning, not because dollar fundamentals are weak, rather the opposite. While the ECB is likely to expand their unconventional monetary policy at the December meeting, both ECB and BOJ policies including negative rates and financial sector regulatory policy, are counterproductive. Consequently, while central bank balance sheets have grown at similar rates, velocity will increase faster in the US rendering monetary policy looser in the US than the Europe, Japan or China. Looser effective monetary policy should push the dollar lower. Later this cycle, as global supply chains are restructured, the US current account deficit is likely to contract leading to a stronger dollar.

Key Recommendations

Long US equities expecting ~15% returns

Overweight cyclicals, market weight technology and communication services, underweight defensives

Upgrading energy

Short equity volatility

Underweight Treasuries, long inflation breakevens and yield curve steepeners

Underweight investment grade credit, marginal overweight high yield

Long emerging market equities, Mexico and Brazil particularly attractive

Market weight export dependent developed markets

Long inflation beneficiaries, commodities and related equities, gold

Barry C. Knapp

Managing Partner

Director of Research

Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC

908-821-7584

bcknapp@ironsidesmacro.com

https://ironsidesmacro.substack.com

https://www.linkedin.com/in/barry-c-knapp/

@barryknapp

This institutional communication has been prepared by Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC (“Ironsides Macroeconomics”) for your informational purposes only. This material is for illustration and discussion purposes only and are not intended to be, nor should they be construed as financial, legal, tax or investment advice and do not constitute an opinion or recommendation by Ironsides Macroeconomics. You should consult appropriate advisors concerning such matters. This material presents information through the date indicated, is only a guide to the author’s current expectations and is subject to revision by the author, though the author is under no obligation to do so. This material may contain commentary on: broad-based indices; economic, political, or market conditions; particular types of securities; and/or technical analysis concerning the demand and supply for a sector, index or industry based on trading volume and price. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. This material should not be construed as a recommendation, or advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any investment. The information in this report is not intended to provide a basis on which you could make an investment decision on any particular security or its issuer. This material is for sophisticated investors only. This document is intended for the recipient only and is not for distribution to anyone else or to the general public.Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although such information is believed to be reliable, no representation is made is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of such information. This information may be subject to change without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics undertakes no obligation to maintain or update this material based on subsequent information and events or to provide you with any additional or supplemental information or any update to or correction of the information contained herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates and partners shall not be liable to any person in any way whatsoever for any losses, costs, or claims for your reliance on this material. Nothing herein is, or shall be relied on as, a promise or representation as to future performance. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS.Opinions expressed in this material may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed, or actions taken, by Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates, or their respective officers, directors, or employees. In addition, any opinions and assumptions expressed herein are made as of the date of this communication and are subject to change and/or withdrawal without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may have positions in financial instruments mentioned, may have acquired such positions at prices no longer available, and may have interests different from or adverse to your interests or inconsistent with the advice herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may advise issuers of financial instruments mentioned. No liability is accepted by Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates or partners for any losses that may arise from any use of the information contained herein.Any financial instruments mentioned herein are speculative in nature and may involve risk to principal and interest. Any prices or levels shown are either historical or purely indicative. This material does not take into account the particular investment objectives or financial circumstances, objectives or needs of any specific investor, and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, investment products, or other financial products or strategies to particular clients. Securities, investment products, other financial products or strategies discussed herein may not be suitable for all investors. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities, investment products or other financial products mentioned herein.The material should not be provided to any person in a jurisdiction where its provision or use would be contrary to local laws, rules or regulations. This material is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose absent the written consent of Ironsides Macroeconomics.© 2020 Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC.