Beggar Thy Neighbor II

Markets solve problems that governments create but trade wars will continue

We will be transitioning the notes to a free summary and full note for paid subscribers format on June 1st. For those of you that require documentation for your internal process we have a description of our products and pricing we can email at your request. Please send a note to my email address, bcknapp@ironsidesmacro.com.

Beggar Thy Neighbor II has evolved from competitive currency devaluations to trade wars, even with a US-China deal the US deficit won’t contract much and the war will continue.

We continue to believe economic reform will overcome authoritarian politics in China and there will be a deal, however, incoming trade data this week was consistent with our view that globalization is no longer expanding. Export dependent economies will continue to struggle with excess capacity.

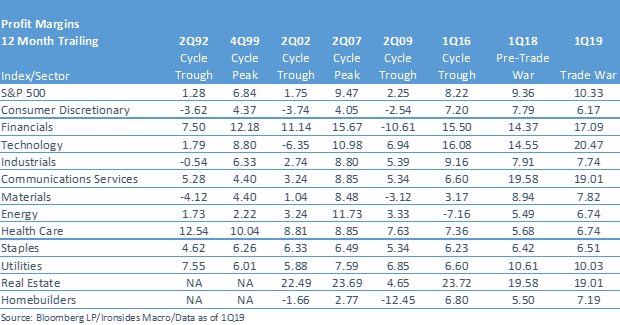

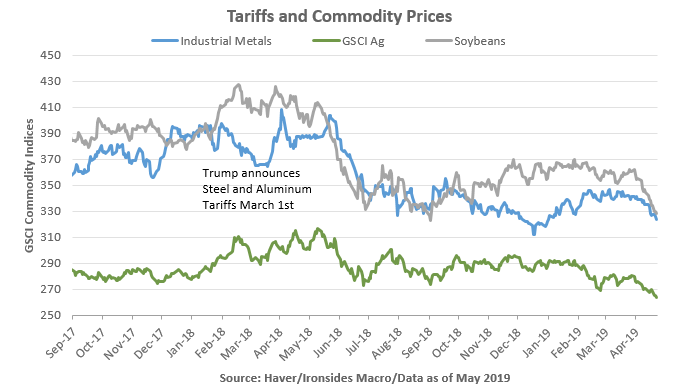

Markets have mitigated much of the ‘deadweight’ economic costs of the Trump administration’s tariffs though Chinese corporate margins, and to a lesser extent US margins, have contracted during the Trump administration trade war.

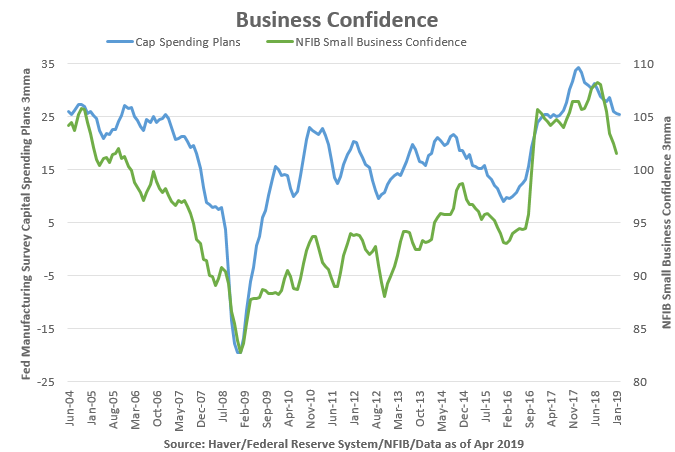

While the direct costs have been largely mitigated by market forces, business confidence has been negatively impacted increasing the risk that the recovery and capital spending and productivity gets derailed by trade policy uncertainty.

Despite this week’s risk off event, our strategic approach remains unchanged, sell export dependent markets on a US-China trade deal due to the likelihood that the recovery in global exports will continue to disappoint.

As we suspected when we wrote “Let’s Make a Trade”¹ two weeks ago, investors’ focus turned quickly from earnings season, improving US data and monetary policy, to the US-China trade negotiations. While reporting and analysis of the US-China negotiations focused on the ‘art of the deal’, China and Taiwan reported soft April exports providing support for our view that even with a robust agreement, the recovery in global trade is likely to be disappointing due to secular economic trends. Because we don’t believe a deal with China will resolve the least important, but most visible and therefore politically toxic issue, the US trade deficit, we are going to focus on illustrating how the market has mitigated much of the damage or deadweight losses resulting from 2018 tariffs on nearly $300 billion of imports. Phrased a bit differently, if there is a deal with China, and the bilateral deficit with China goes down, the total US deficit, at least in the intermediate term, will not, and as a consequence the trade wars will continue.

¹https://ironsidesmacro.substack.com/p/lets-make-a-trade-deal

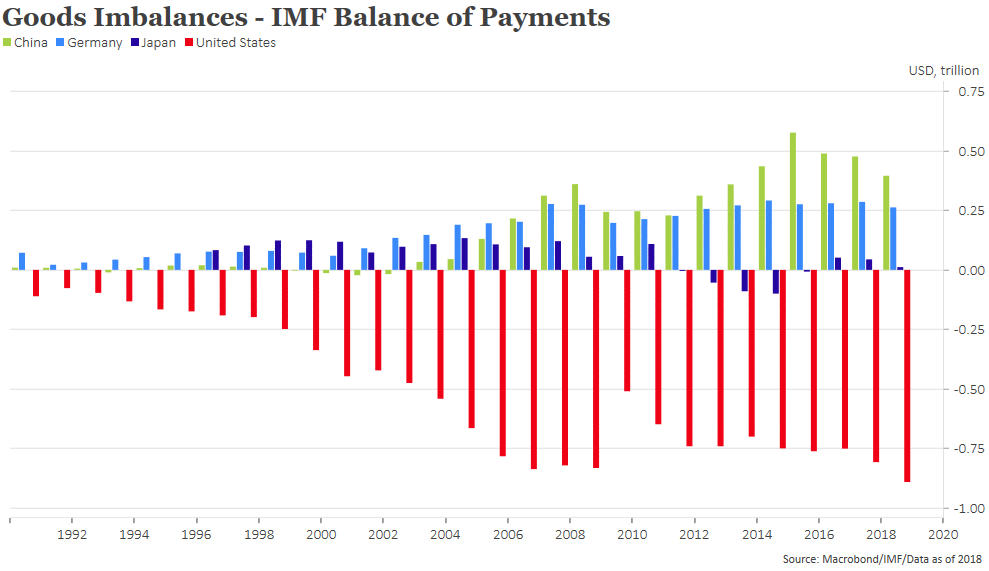

The 1990-2010 period of rapid growth of global trade driven by the 120% increase in the supply of labor left the developed world deeply in debt with lower nominal growth to service the debt. Like the post-WWI period, policymakers have engaged in competitive devaluations, capital controls and financial repression. Early in the post-crisis period, rather than barriers to trade, policymakers balkanized capital accounts. The Trump administration’s trade war was an inevitable lagged response to both the labor supply shock and export dependent nations trade protection policies. As a consequence, and because tariffs have been effective politics through the history of the US, as soon as the ink is dry on a trade agreement with China the focus will shift to Germany, Japan and any other country with a large US trade surplus. A case in point occurred on Thursday night as the markets focused on the Chinese delegation arrival, the Treasury Department announced they were vetting more trading partners for currency manipulation and called out Vietnam specifically.

To be sure, global trade, even before the Trump administration’s trade war, was far from free and the over the last twenty years there was a lack of reciprocity as the US lowered trade barriers. That notwithstanding, as a result of excess capacity in global tradable goods, tariffs intended to offset aggregate imbalances are likely to be ineffective. While we believe the era of global trade exceeding output growth is over, markets will overcome most of the deleterious effects of trade barriers, and the aggregate economic loss will not cause a global recession though periodic macro shocks are likely. Export dependent economies will continue to struggle with excess capacity and their equity markets should be structural underweights; however, the ‘deadweight’ economic loss to the US of increased trade barriers is likely to be small even in the event that Chinese political authoritarianism proves a greater force than the strong economic necessity of reform and their access to the largest consumer market is impaired.

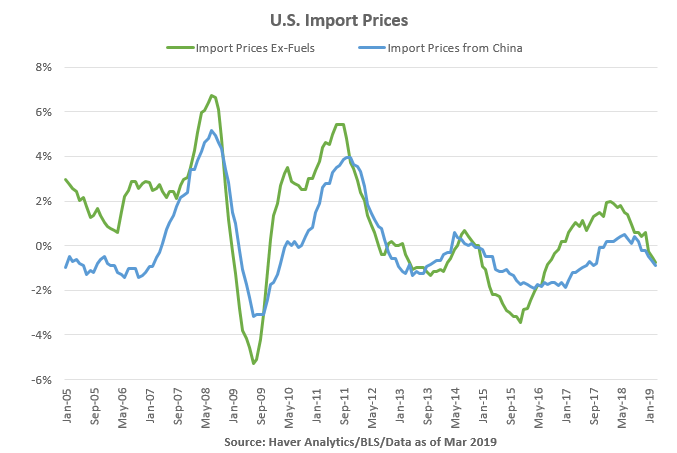

One rigorous analysis of the effects of the tariffs the Trump administration placed on $283 billion of imports in 2018 titled “The Impact of the 2018 Trade War on U.S. Prices and Welfare”² concluded the loss of real income of $1.4 billion per month or 10 basis points of total income. Beyond their bottoms-up, product specific analysis, we would add that Chinese import prices were rising at a 0.2% year-on-year rate in January 2018 when the first wave of tariffs were implemented and are now falling 0.9%. Of course, many goods can be sourced outside of China so it is worth considering that total ex-fuels import prices dropped from 2.0% to -0.8% over the same period. One of the key arguments for a proposed border-adjustment tax provision of corporate tax reform was that exchange rate adjustments would offset the cost to consumers. Given the increase in the trade weighted dollar during Trump’s trade war of 7.39% and a 5.4% decline in the yuan that has effectively mitigated the cost of tariffs, the currency adjustment thesis has merit. Still, were the yuan to fall sharply in response to a 25% tariff on all Chinese imports, outflow pressures like August of 2015 could lead to a major tightening of financial conditions and expose the latent bad loan problem in the banking system. This is one potential macro shock from the Trump trade war.

²https://www.nber.org/papers/w25672

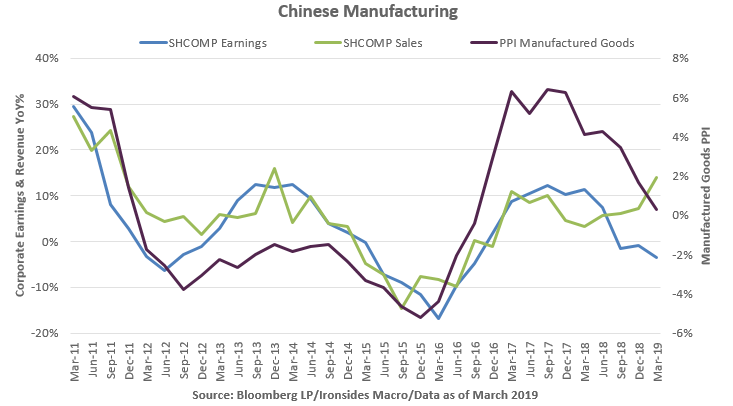

When the authors of the aforementioned analysis reached the following conclusion it appears they hadn’t considered the impact on the Chinese corporate sector:

“although in principle the effect of higher tariffs on domestic prices could be offset by foreign exporters lowering the pre-tariff prices that they charge for these goods, we find little evidence of such an improvement in the terms of trade up to now, which implies that the full incidence of the tariff has fallen on domestic consumers so far.”

In 1Q18 revenues for the Shanghai Composite increased 3% y/y, in 1Q19 sales growth had improved to +14%, however, earnings growth had slowed from +10% in 1Q18 to -1% in 1Q19. Manufacturing producer prices increased 4.13% in 1Q18, in 1Q19 only 0.3%. If it looks like Chinese state owned enterprises absorbing price pressures in their margins, it most assuredly is just that. Market participants learned this lesson last spring when the significantly larger reaction in equities relative to government securities and currencies, as well as significant underperformance of Chinese stocks relative to the US, sent a clear signal that the market believed the costs of tariffs would be absorbed in profit margins of exporters.

This is not to say US corporates emerged unscathed from the trade war. Margins contracted for the consumer discretionary, industrials and materials sectors over the course of the year despite exceptionally strong revenue growth and minimal inflationary pressures. We would be a bit careful about reaching any definitive conclusions from sector margins given compositional changes to the consumer discretionary, technology and communication services sectors in 2018 as well as the corporate tax reform. Still, consistent with relative stock price performance, margins continued to expand for the S&P 500, while they contracted for Shanghai Composite during the imposition of the 2018 tariffs.

Of course, in agriculture where the Chinese retaliated there were offsetting price declines and the economic loss was borne by American farmers. The overarching theme is that product and exchange rate markets tend to deflate in response to tariffs on goods leading to economic losses for producers. Let us be clear, tariffs are deflationary.

This brings us to the greatest risk from the Trump trade war, business confidence, capital spending and the recovery in productivity. The chart below shows a steady deterioration in business confidence since the Trump administration began the trade war. Because we smoothed the data series to make the chart easier to interpret, it masks a quick drop last spring when the administration initiated steel and aluminum tariffs and NAFTA was negotiated. Subsequent recovery due to the policy feedback loop. Another leg lower ahead of the threat of larger tariffs at year-end. The chart also does show the stabilization the last two months as the US economic outlook improved and a deal with appeared China likely. The reason we decided to show the data smoothed was to illustrate that following the first post-crisis year of 3% GDP, 20% earnings growth, profit margins at all-time highs, a major reduction in corporate tax rates, and a strong recovery in productivity, small business confidence and manufacturing capital spending plans have been eroding steadily. The erosion of confidence impact on capital investment is a bit difficult to unpack. Equipment and structures investment slowed in 2H18, however intellectual property products remained strong. Structures are the biggest beneficiary of corporate tax reform and are the most confidence dependent capex category. The deceleration from from 14.2% 1H18 annualized growth to -3.7% in 2H18 could be ordinary volatility in this uneven series, but, given the drop in confidence structures investment may have been collateral damage from the trade war. Our capital spending models for equipment and intellectual property products, even with the pullback in capital spending plans, are still looking for growth nearly double the weak ten-year trend, however, business confidence is the biggest risk to the administration’s trade policy strategy.

This week, rather than beginning with the historical perspective, we are going to end with some thoughts on the trade wars of the past. There is one key difference between Beggar Thy Neighbor I in the ‘20s and ‘30s and today. Both began with competitive devaluations and evolved into tariffs on goods with the US playing a central role in phase two. The difference is that the US had the largest trade surplus in the ‘30s, today the largest deficit. As we mentioned in our note two weeks ago, “Clashing Over Commerce” by Douglas Irwin is fascinating and quite helpful. Irwin notes that exports were roughly a third of today’s level when a bill to help farmers morphed into the notorious Smoot Hawley tariffs. Furthermore, tariffs were specific dollar amounts rather than ad valorem percentages as is the case today. The bill only raised the average tariff ~5% from a level that was already in the 30’s. Because of deflation resulting from Treasury Secretary Mellon’s bank ‘liquidationist’ policy and resulting collapse in the monetary base, the average tariff was above 60% years later. There was undoubtedly a business confidence shock, but the direct impact on economic activity was likely smaller than the bill’s infamous legacy would leave one to believe. Perhaps the most underappreciated implication of Smoot Hawley was Congress acquiescing its constitutional responsibility for trade policy to President Roosevelt. That power never returned to Congress though if things end badly this time, perhaps Congress will take the power back.

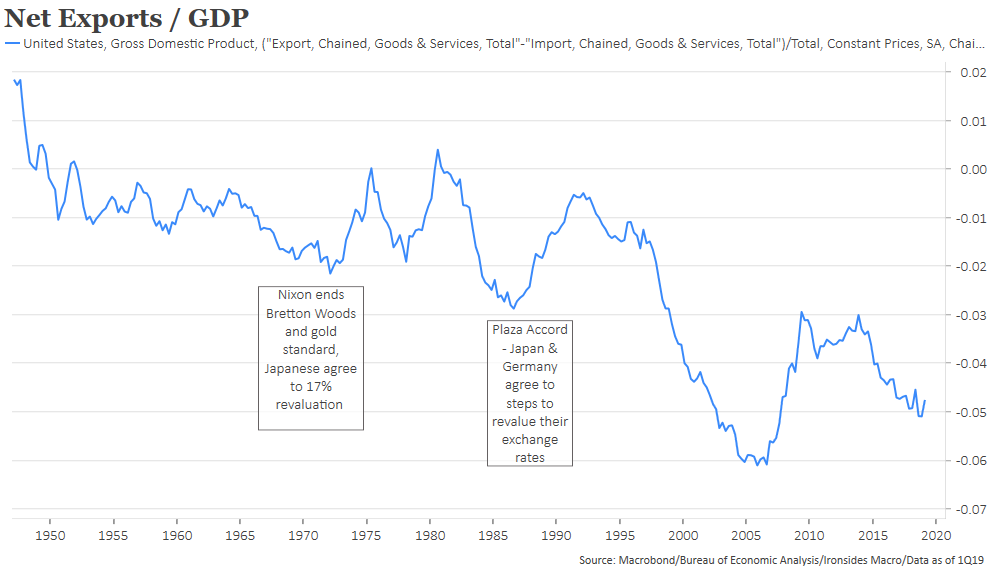

The post-war trade environment is misunderstood as well. While the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate regime was structured to facilitate a recovery in global trade, the recalcitrant British Empire only begrudgingly agreed to small reductions in tariffs. This time post-war inflation reduced tariffs. As devastated Japan and Germany recovered in the following decades, their trade surpluses surged, however, the US trade account remained in small surplus until the first energy deficits in the late ‘60s. Under Bretton Woods countries with large surpluses were required to revalue their currencies, in the late ‘60s France and the UK devalued and while the Germans were concerned about importing US inflation, the Japanese refused to revalue. On an August 1971 Sunday night, President Nixon told the American public the dollar was no longer redeemable for gold and the Japanese were forced into a 17% revaluation that the Germans also agreed to. History repeated in the early ‘80s, a collapse in the US energy trade deficit following energy sector deregulation and a sharp recovery in production sent the dollar soaring in the early ‘80s, however the goods deficit went to unprecedented levels and the Japanese and Germans agreed to currency revaluation in the Plaza Accord. After both of these trade wars that ended with currency deals, the US trade deficit contracted for several years only to have market forces overtake government policies. Trade wars are more common than not.

We expected a shallow pullback in the S&P 500 and larger correction in export dependent economies following a US-China trade deal as it became clear that the recovery in trade was disappointing. Although we did not address last minute brinkmanship, this week’s developments have not changed our strategy. As of Friday morning, the S&P 500, German Dax and Japanese Nikkei indices were 4% from their peaks while the Shanghai Composite was 13% off its late April’s level. The inversion of the VIX curve - short term above intermediate implied volatility - implies that investor positioning will provide the fuel for new highs if a deal is reached. Our former derivative colleagues often refer to term structure as the new skew. In other words rather than buying out of the money puts amidst macro shocks, investors buy VIX calls. The outperformance of Germany and Japan implies investors haven’t discounted the trade wars continuing and the continued drag of excess global goods capacity. Assuming there is a deal as we expect, we would use the rally to reduce exposure to export dependent markets. Sell some long term US Treasuries as well.

Barry C. Knapp

Managing Partner

Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC

908-821-7584

https://www.linkedin.com/in/barry-c-knapp/

@barryknapp

This institutional communication has been prepared by Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC (“Ironsides Macroeconomics”) for your informational purposes only. This material is for illustration and discussion purposes only and are not intended to be, nor should they be construed as financial, legal, tax or investment advice and do not constitute an opinion or recommendation by Ironsides Macroeconomics. You should consult appropriate advisors concerning such matters. This material presents information through the date indicated, is only a guide to the author’s current expectations and is subject to revision by the author, though the author is under no obligation to do so. This material may contain commentary on: broad-based indices; economic, political, or market conditions; particular types of securities; and/or technical analysis concerning the demand and supply for a sector, index or industry based on trading volume and price. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. This material should not be construed as a recommendation, or advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any investment. The information in this report is not intended to provide a basis on which you could make an investment decision on any particular security or its issuer. This material is for sophisticated investors only. This document is intended for the recipient only and is not for distribution to anyone else or to the general public.

Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although such information is believed to be reliable, no representation is made is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of such information. This information may be subject to change without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics undertakes no obligation to maintain or update this material based on subsequent information and events or to provide you with any additional or supplemental information or any update to or correction of the information contained herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates and partners shall not be liable to any person in any way whatsoever for any losses, costs, or claims for your reliance on this material. Nothing herein is, or shall be relied on as, a promise or representation as to future performance. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS.

Opinions expressed in this material may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed, or actions taken, by Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates, or their respective officers, directors, or employees. In addition, any opinions and assumptions expressed herein are made as of the date of this communication and are subject to change and/or withdrawal without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may have positions in financial instruments mentioned, may have acquired such positions at prices no longer available, and may have interests different from or adverse to your interests or inconsistent with the advice herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may advise issuers of financial instruments mentioned. No liability is accepted by Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates or partners for any losses that may arise from any use of the information contained herein.

Any financial instruments mentioned herein are speculative in nature and may involve risk to principal and interest. Any prices or levels shown are either historical or purely indicative. This material does not take into account the particular investment objectives or financial circumstances, objectives or needs of any specific investor, and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, investment products, or other financial products or strategies to particular clients. Securities, investment products, other financial products or strategies discussed herein may not be suitable for all investors. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities, investment products or other financial products mentioned herein.

The material should not be provided to any person in a jurisdiction where its provision or use would be contrary to local laws, rules or regulations. This material is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose absent the written consent of Ironsides Macroeconomics.

© 2019 Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC.