Is the Income Recession Ending?

Stealth recession, who will buy the bills, death of the repo man, macro muddle

Discussing Liquidity Climate Change on CNBC

The Stealth Recession

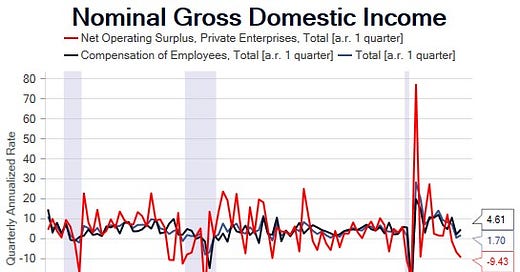

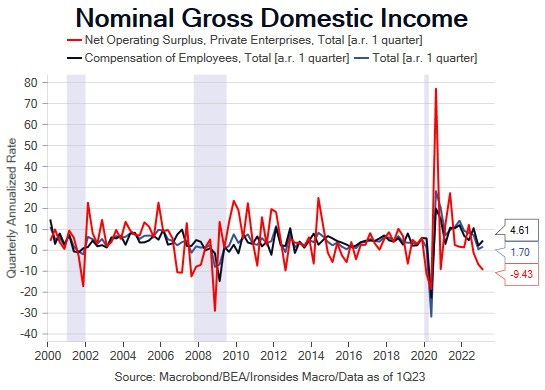

What if a recession began in October of last year and is ending? With the first revision of 1Q23 GDP, we also received the first estimate of 1Q23 gross domestic income at -2.3% following a 3.3% contraction in 4Q22. We consider GDI a better measure of the business cycle (see the link below from a former Fed staffer), particularly for investors. Income drives investment and consumption, not the BEA’s attempts to sum expenditures on goods and services. The two measures of growth should be equal over time, but given revisions and an increasingly complex services sector, GDI has a superior track record in catching turning points. The official recession dating entity, the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), is unlikely to define the two-quarter decline in gross domestic income as a recession due to the resilience of the labor market and the negative contribution of government agencies (the Fed losses).

That said, the primary driver of the two-quarter contraction in gross domestic income was a 6.7% drop in the net operating surplus for private enterprises in 4Q23, followed by a 9.4% plunge in 1Q23. While this series is exceptionally volatile, it fits the trajectory of S&P 500 earnings, and implies that even if we were not in a NBER recession, we are in a real, but not nominal, corporate sector income recession. Nominal compensation slowed but remained positive, though on a real basis was likely marginally negative. While this is rearview mirror analysis, it further increases our confidence that the October low in the S&P 500 will not be retested. Let us explain.

The S&P 500 is a leading indicator in the Conference Board Index. Its 27% decline from January through October, prior to the two-quarter contraction in real gross domestic income, was midway between the median decline associated with a post-war recession of 24% and average drop of 30%. While we’ve characterized the ‘22 correction as a Fed policy normalization correction, the two-quarter contraction in GDI implies the drawdown was a recession-related bear market. The contraction in GDI, and private enterprise operating surplus in particular, fits with the trajectory of S&P 500 earnings, and because nominal GDI never went negative during the income ‘recession’, the earnings decline was smaller than the median decline of 14% or average of 18% for a post-war recession. Using S&P 500 expected earnings, the tentative trough was -5% at the beginning of 1Q23 reporting season in late April, a decline similar to the 4.3% drop during the brief 1980 Carter Credit Controls recession when real GDP contracted 2.2% but nominal GDP increased 4.7%. The apparent bottom of earnings is also supported by the leading indicator, net revisions, bottoming in November ‘22 and moving higher during 1Q23 reporting season. While the timing of the S&P 500 low relative to the end of the recession (assuming it is ending and we are not heading for a double dip due to aggressive monetary policy tightening, as in the early ‘80s) was early given the median of 105 days, the range is wide and in several cases the market bottomed 5-6 months prior to the end of the recession.

The Income- and Expenditure-Side Estimates of U.S. Output Growth