A New Paradigm

The high velocity rally in real rates (TIPS yields) over the last 2 1/2 weeks likely marks a paradigm shift inasmuch as the catalyst was not a change in the growth outlook, though it is improving, nor was it attributable to expectations of changes in the stock, or flow of Federal Reserve large-scale asset purchases, instead the signal from the Treasury market is that there is indeed a limit to deficit financed government spending. The implications for markets are profound, correlations that have become second nature to investors like equity prices and rates, real rates and gold, are likely to change. If fiscal policy continues to exert a greater influence on real rates than monetary policy, these correlations should change due to differences of economic impact and relative credibility and flexibility of fiscal and monetary policy. Our characterization of the pandemic as an inflationary shock is the antithesis of the Fed’s view, however given that the primary source of disinflation for three decades was core goods prices due to the integration of China into global supply chains and the high probability that the pandemic will be an accelerant for ‘just-in-case’ supply chain management, the shock to goods prices is unlikely to prove transitory. Service sector prices are likely to recovery quickly to levels above the Fed’s average inflation target as the effects on consumer behavior from the pandemic recede. Later in this week’s note, we will demonstrate how broad measures of labor market slack show a much tighter labor market than the Fed talking point that there are 10 million fewer workers implies. Consequently, right at the point when the primary source of disinflation is reversing, policymakers decided to the test the limits of deficit financed government spending. This is consistent with the history of policy responses, for both fiscal and monetary policymakers it is far easier to initiate stimulus than to withdraw it. We will leave the implications of the real rate regime change for modern monetary theory for another day, suffice it to say they are ominous. During the reflation phase of this paradigm shift, rates and equities can, and likely will, rise simultaneously except when the velocity of the rate move becomes extreme, leading to yet another volatility of volatility risk-off episode. These episodes, like this week’s, will continue to be offset by the structure of the equity volatility market, by Thursday’s close with the S&P only 3% off its high, the front month VIX future was 29% and our aggregate measure of equity risk had spiked from 0.6 standard deviations above its longer-run median prior to the real rate spike, to 1.3. While a 3% move is not a compelling entry point, we see no reason to reduce risk in our reflation related positions.

Choking on Supply

In this week’s semiannual monetary policy report, Fed Chairman Powell attributed the rally in rates to an improving economic outlook. This attribution is overly simplified and broadly incorrect. Prior to the global financial crisis, changes in the economic outlook were a significant factor in determining the level of real rates (TIPS yields). With the launch of large-scale asset purchases post-crisis, and associated real rate and volatility suppression, the stock and the flow, as well of expectations of the flow of asset purchases, became the major determinant of the level and direction of real rates. The economic outlook still played a role, but only in terms of what it meant for the Fed policy reaction function. For those who at that time were struggling to understand this change, the Taper Tantrum in 2013 and associated rally in 10-Year real rates from -0.72% in April to +0.91% by September, was stark evidence Fed asset purchases were suppressing rates. Two more smaller shocks in January and September of 2018 at the beginning, and towards the end of the Fed balance sheet contraction, were evidence that the portfolio balance channel worked through asset prices, but the effects were transitory, and the policy could not be reversed without disrupting markets. January 2021, following the Georgia Senate elections, marked another inflection point in the age of interventionism in the most important price in a market economy. The delayed blue wave scenario sparked a transitory spike in real rates that was exacerbated by several Regional Federal Reserve Bank Presidents discussing the potential for reducing asset purchases in 2021. The rally ended with assurances from the Federal Reserve Board leadership that they were not even ‘thinking about thinking about’ tapering. That 17bp move was just a warning sign for the 45bp two-week spike that has all the makings of the Treasury market choking on supply. The average duration of Fed QE purchases is 6 years, over the last 3-months 5-year real rates are down 47bp, during the 2-week spike they rallied 31bp. In contrast, 30-year real rates are +45bp over 3-months, and +45bp over the last 2 weeks. The same pattern can be seen in implied volatility, it is super cheap for 2-year Treasuries that are largely influenced by Fed rate policy, cheap at the 5-year point that is most sensitive to QE, and most expensive for 10-year Treasuries where convexity mortgage hedging pressures are greatest. In other words, even where the Fed influence is greatest, Treasury supply more than offset Fed demand, and where the Fed influence was smaller, the market is choking on Treasury supply. The rally in nominal Treasuries began with inflation expectations (breakevens), however as expectations of the size of the Biden Rescue Plan increased towards the full $1.9 trillion and the details revealed significant increases to longer-run entitlement spending, expectations of additional deficit financed government spending from this bill and the upcoming Build Back Better Plan sent the first warning signs that there are Treasury borrowing capacity limits. Total deficit financed fiscal spending since the pandemic began, assuming $1.9 trillion for the Rescue Plan, will be $5.3 trillion, while Fed large-scale asset purchases are a ‘paltry’ $2.8 trillion. Fed Chairman Powell’s assurances had little effect on the rates rally this week, it finally took a breather Thursday night after the Senate Parliamentarian ruled against inclusion of the minimum wage hike, perhaps signaling there may be some political constraints on deficit financed government spending after all.

While we do not expect the Fed to even begin discussing tapering asset purchases until the June 16th FOMC meeting at the earliest, they now have potentially two problems to discuss at the March 17th meeting that could result in incremental easier policy. The first is the flood of cash from the Treasury General Account (TGA) that based on the terms of the August 2019 debt ceiling deal needs to be reduced from its current $1.57 trillion to $120 billion by August 1st. One step is to extend the exemption of bank reserves and Treasuries from the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR). Chairman Powell received numerous questions from the Senate and House last week, it appears that there is little political opposition, though we are concerned that Fed Governor Brainard and Treasury Secretary Yellen could oppose the extension. The second issue is the velocity of the rates rally, earlier in the year there was some discussion at the Fed for another maturity extension program from 6-year average duration to as much as 12-years. There is plenty of evidence of the former, we suspect the rates rally would need to continue at a similar pace for the Fed to launch another Operation Twist.

The Mandate

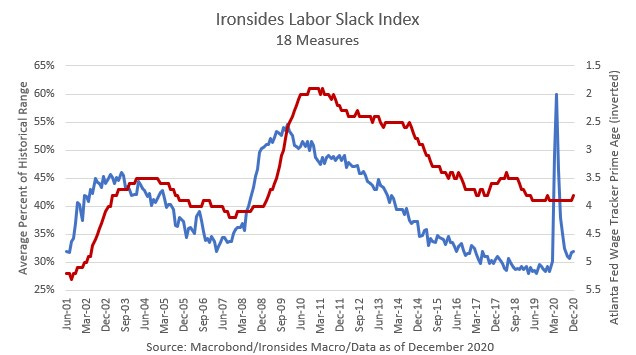

We heard from Fed Chairman Powell and every other Fed speaker that there are 10 million fewer workers due to the pandemic. Excuse us for nitpicking, but there are 9.9 million fewer nonfarm workers and 8.7 million fewer private sector workers. A good portion of the difference is public sector educators. The real question is, what is the amount of slack? During the policy impaired labor market recovery from 2009-2014, as the U3 unemployment rate declined, the Fed dug up a myriad of indicators of slack as justification for easy policy. At BlackRock we had the Yellen ‘spider’ chart of slack indicators and shortly after Powell became Chairman, we created a Powell Slack Index at Guggenheim. Now that they seem to be singularly focused on that 10 million talking point, we reconstructed our slack index using 18 indicators including, U3 unemployment, U6 underemployment, short & long term unemployment rates, labor force participation rates (aggregate, prime, female), employment ratios, job openings, quits, and layoff rates, disability, reallocation, permanent job losers, unemployment insurance, duration of unemployment, and a few other indicators. We then took the long-term range for each of the indicators and derived an aggregate percent of slack index. This approach to measuring slack leads our preferred measure of wage growth, the Atlanta Fed Wage Tracker.

Additionally, the rapid recovery from the pandemic, even with the 4Q20 stall, is at a level of diminished slack it took 7 years to reach during the last cycle (2016). The December reading was 31.9%, that is higher than 30.6% in October and 28.3% in January 2020 that was close to the cycle low of 27.9% in March 2019, prior to the most acute phase of the trade war. The absence of slack might be surprising, some of the positive contributors are the job openings, quits and layoff rates and robust labor market dynamism hinting that expanded unemployment insurance is impairing the recovery. Additionally, for all the discussion about the impact of closed schools on female participation rates, prime age female participation is 74.8%, down from 76.8% in January but right on its average of 74.9% during the 2009-2019 expansion. Given the concentration of job losses in pandemic impaired sectors, accelerating vaccination rates, plunging case counts and the removal of non-pharmaceutical interventions from the coastal collectivists, our slack index could be back to pre-pandemic lows later this year even with the disincentive of generous unemployment insurance benefits extending until at least 3Q21.

Capex Recovery Momentum

Last week’s data was constructive for the second of our 2021 tailwinds, a robust and durable recovery in capital spending. While there are significant policy risks to our longer-term outlook, namely the Biden Administration and state governments attempting to pay for pandemic relief and related expansion of the social welfare safety net with taxes on capital and corporations, the cyclical recovery outlook is improving rapidly. Last week’s regional Fed manufacturing surveys from Dallas, Richmond and Kansas City confirmed the Empire State and Philadelphia increases in 6-month forwards capital spending plan outlooks. Those plans have recovered to where they were prior to the May 2019 tariff tweet that caused a negative business confidence shock. The January durable goods report showed continued strong momentum for core capital goods orders and shipments and the revision to 4Q20 GDP had an upward revision to intellectual property products investment that was consistent with the recovery in S&P 500 research & development expense we covered in last week’s note.

The focus next week will be the labor market, as we have been noting the claims data since the pandemic programs were extended and $300/week supplemental benefits were added the recovery momentum appears to have slowed. We are likely a month or two away from the effects of falling case counts, increased vaccinations and reduced non-pharmaceutical interventions increasing job creation. The labor market where our economic tailwinds and policy risks are clashing early in the recovery. Consequently, the labor data may not be particularly friendly for markets next week. Any additional pullback should be used to add risk.

Key Investable Themes & Beneficiaries:

Global Manufacturing and Trade Recovery: Industrials, Materials, EM Equities

Capital Spending Boom in 2021: Technology, Industrials, Healthcare

Reflation: Materials, Financials, Energy, Small Caps, Inflation Breakevens

Barry C. Knapp

Managing Partner

Director of Research

Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC

908-821-7584

bcknapp@ironsidesmacro.com

https://ironsidesmacro.substack.com

https://www.linkedin.com/in/barry-c-knapp/

@barryknapp

Reading List

“The Theory That Would Not Die: How Bayes’ Rule Cracked the Enigma Code, Hunted Down Russian Submarines & Emerged Triumphant from Two Centuries of Controversy”, Sharon Bertsch McGrayne

“A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 2, Book 1, 1951-1969”, Allan H. Meltzer

“Human Action, The Scholar’s Edition”, Ludwig von Mises

“A Great Leap Forward, 1930s Depression and US Economic Growth”, Alexander J. Field

“1493, Uncovering the New World Columbus Created”, Charles C. Mann

“Great Society, A New History”, Amity Shlaes

“The Second Machine Age”, Erik Brynjolofsson, Andrew McAfee

“Judgement in Moscow, Soviet Crimes and Western Complicity”, Vladimir Bukovsky

“1931, Debt, Crisis and the Rise of Hitler”, Tobias Straumann

“The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers”, Paul Kennedy

“Capitalism in America, A History”, Alan Greenspan & Adrian Woolridge

“Diversity Explosion, How New Racial Demographics are Remaking America”, William H. Frey

“Clashing Over Commerce, A History of US Trade Policy”, Douglas A. Irwin

“Destined for War, Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap”, Graham Allison

“The Constitution of Liberty”, F.A. Hayek

“Grand Pursuit, the Story of Economic Genius”, Sylvia Nasar

“The Fourth Industrial Revolution”, Klaus Schwab

“Trade Wars Are Class Wars”, Matthew C. Klein & Michael Pettis

“Showdown at Gucci Gulch, Lawmakers, Lobbyists, and the Unlikely Triumph of Tax Reform”, Jeffrey H. Birnbaum and Alan S. Murray

This institutional communication has been prepared by Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC (“Ironsides Macroeconomics”) for your informational purposes only. This material is for illustration and discussion purposes only and are not intended to be, nor should they be construed as financial, legal, tax or investment advice and do not constitute an opinion or recommendation by Ironsides Macroeconomics. You should consult appropriate advisors concerning such matters. This material presents information through the date indicated, is only a guide to the author’s current expectations and is subject to revision by the author, though the author is under no obligation to do so. This material may contain commentary on: broad-based indices; economic, political, or market conditions; particular types of securities; and/or technical analysis concerning the demand and supply for a sector, index or industry based on trading volume and price. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. This material should not be construed as a recommendation, or advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any investment. The information in this report is not intended to provide a basis on which you could make an investment decision on any particular security or its issuer. This material is for sophisticated investors only. This document is intended for the recipient only and is not for distribution to anyone else or to the general public.Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although such information is believed to be reliable, no representation is made is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of such information. This information may be subject to change without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics undertakes no obligation to maintain or update this material based on subsequent information and events or to provide you with any additional or supplemental information or any update to or correction of the information contained herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates and partners shall not be liable to any person in any way whatsoever for any losses, costs, or claims for your reliance on this material. Nothing herein is, or shall be relied on as, a promise or representation as to future performance. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS.Opinions expressed in this material may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed, or actions taken, by Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates, or their respective officers, directors, or employees. In addition, any opinions and assumptions expressed herein are made as of the date of this communication and are subject to change and/or withdrawal without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may have positions in financial instruments mentioned, may have acquired such positions at prices no longer available, and may have interests different from or adverse to your interests or inconsistent with the advice herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may advise issuers of financial instruments mentioned. No liability is accepted by Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates or partners for any losses that may arise from any use of the information contained herein.Any financial instruments mentioned herein are speculative in nature and may involve risk to principal and interest. Any prices or levels shown are either historical or purely indicative. This material does not take into account the particular investment objectives or financial circumstances, objectives or needs of any specific investor, and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, investment products, or other financial products or strategies to particular clients. Securities, investment products, other financial products or strategies discussed herein may not be suitable for all investors. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities, investment products or other financial products mentioned herein.The material should not be provided to any person in a jurisdiction where its provision or use would be contrary to local laws, rules or regulations. This material is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose absent the written consent of Ironsides Macroeconomics.© 2021 Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC.