Apologies for the delay in the note this week, it was unavoidable due to a busy travel schedule. Unfortunately, it may happen a few more times in the coming months.

Doing Harm

‘It’s never different this time, but it’s never the same as the last time.’

“Banking conditions have broadly improved since March”, Chairman Powell

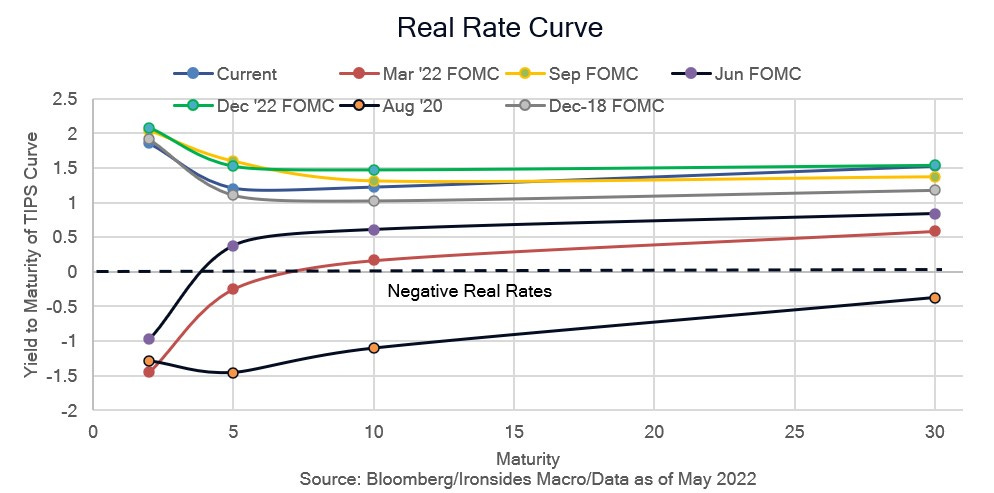

The September ‘22 FOMC meeting, when the Fed hiked rates 75bp for the third consecutive time and increased their terminal rate forecast in the quarterly summary of economic projections 80bp, had wide-reaching effects. It destabilized exchange rates and exacerbated the energy crisis for large importers, degraded liquidity in USTs, widened mortgage spreads and left the banking system stranded with securities portfolios comprising one third of their assets with yields below the (future) cost of their liabilities. Slowing the pace of hikes stabilized markets, however, we now know that when the policy rate exceeded 3% it destabilized the banking system. When the Chairman hinted at stepping up the pace of hikes at the semi-annual monetary policy report to Congress, and following the last two 25bp hikes, the market response was similar to the September meeting. The Committee doesn’t seem to have learned its lesson, even this weekend St Louis Fed President Bullard suggested more hikes were necessary. While no FOMC participant has assigned any role for monetary policy in banking system instability, we are expecting them to do so, eventually. An acknowledgement that monetary policy and macro prudential policy cannot be separated in the current environment is one potential turning point for markets and the growing risk of a nonlinear tightening of credit.

We heard echoes from the financial crisis all week. No one from our senior circle in Lehman Brother’s capital market division believed our issues were resolved when JPMorgan struck their sweetheart deal with the Treasury and Federal Reserve to acquire Bear Stearns. When Fed Chairman Bernanke told Congress subprime was ‘contained’ our mortgage research department had concluded that 2/3’s of zip codes had at least 60% subprime origination during the previous 18 months, so consequently we knew subprime was not ‘contained’.

JPMorgan’s First Republic deal did not stabilize the banking system and banking conditions have not improved since March. Sure, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve could hardly say the banking system was unstable, but a discussion of the implications of a large contraction of bank credit seemed warranted. Bank deposit growth is -5%, assuming a debt ceiling deal, even if it is a suspension to the year-end budgeting process, will likely drain ~$500 billion primarily out of bank deposits. Even if we exclude the first two weeks following the Silicon Valley Bank collapse, flows into government money market funds are averaging $25 billion more than the pre-SVB weekly inflows. Were that pace to persist through the year, assuming the bulk is leaving banks, deposits would fall by an additional $750 billion. Former FHFA Director Mark Calabria’s forecasted another $1 trillion during a CNBC interview last week. One client last week postulated there was no CD rate a regional could bid to bring funds back from government money funds. Bank credit growth has already slowed from 9.6% prior to the September FOMC meeting to 2%. If credit growth converges with deposit growth, as was the case pre-pandemic, the process is unlikely to be linear on the way to a 10% contraction in bank credit (securities and loans). There is a potential cushion: bank reserves remain elevated, loan to deposit ratios are near historic lows, and the credit quality of bank assets is the antithesis of the financial crisis. That said, it seems clear that regional banks have only one option, and that is to shrink their asset base.