Disinflation, Reflation and Inflation: '60s Déjà Vu All Over Again

Fiscal, Monetary & Exchange Rate Policies in the '60s are back

The ‘20s Expansion, Echoes of the ‘60s Policy Errors

“The years 1961–71 were a part of the Keynesian interlude dominated by a strong belief that government was responsible for stabilizing an unruly private sector. The distinguishing characteristics were two related beliefs: (1) that policymakers could adjust their actions in a timely way to smooth fluctuations, and achieve full employment with high growth and low inflation, and (2) that policymakers could choose and achieve the right, possibly optimal, combination of inflation and full employment. Keynesian economists called their program “the new economics” to signify the departure from prevailing orthodoxies.”

“A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 2, Book 1, 1951-1969”, Allan H. Meltzer

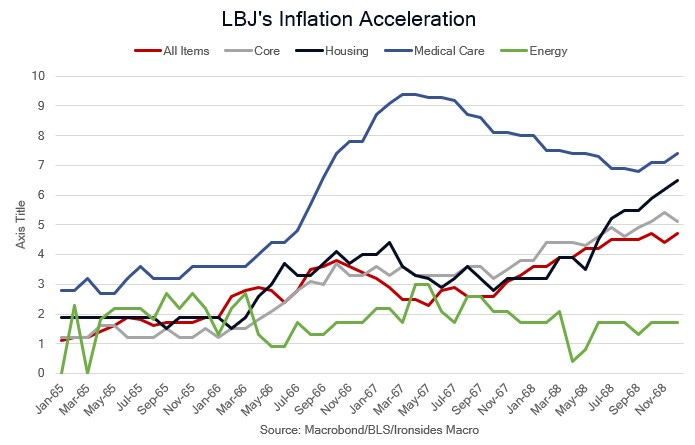

The 1960 presidential election took place amidst a recession that began in April and ended in February 1961. The Kennedy Administration brought new-Keynesians into the Federal Reserve and throughout the administrative state. While their earliest actions were to accelerate depreciation schedules and later cut tax rates, which contributed to strong investment, ‘new-economics’ did not differentiate between private sector supply-side tax cuts and government demand via increased spending that led to a doubling of outlays to pay for the Great Society and the Vietnam War. The Kennedy and later LBJ administrations tipped the scales of Chairman Martin’s Federal Reserve, which he described as independent within, not of, the government, towards the unemployment mandate of the Employment Act of 1946. Martin believed that if Congress voted to increase spending, the Federal Reserve had an obligation to finance debt issuance. JFK’s Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors Walter Heller “went to Washington thinking we ought to end the independence of the Federal Reserve”. That turned out to be unnecessary given Martin’s acquiescence and the personnel changes at the Board.

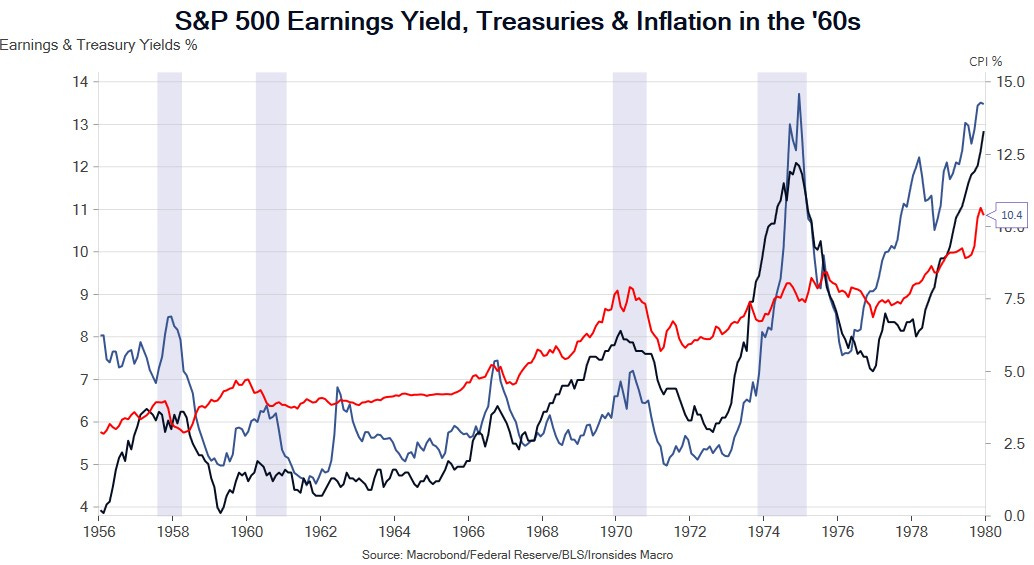

Expansive monetary and fiscal policy in the ‘60s that sparked a regime change from disinflation to reflation started well for investors and the public. Despite uneven post-war growth, 5 recessions from ’46 to ’60, tepid nonresidential fixed investment, sluggish S&P 500 earnings growth, and weak credit growth attributable to a restrictive bank regulatory environment and financial repression, the S&P 500 PE increased from 7 at the end of the war to 20 by the time JFK was elected.

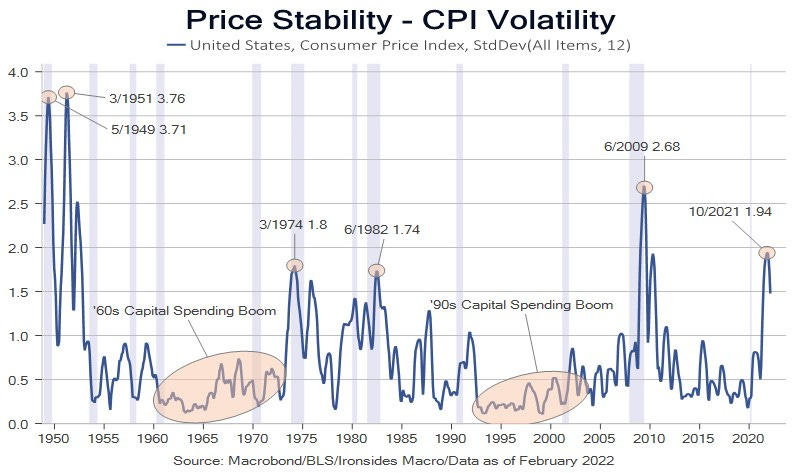

The combination of accommodative fiscal and monetary policy in the ‘60s led to stronger nominal GDP and earnings growth and while equities were rich, returns were decent due to stronger growth. Faster growth in the early ‘60s, which at the time was the longest business cycle in US history, contributed to stronger capital investment and high equity market valuations. Earnings growth averaged 12.4% annualized for the first half of the business cycle before slowing sharply to 1.7% in the second half of the cycle, underscoring the different impact of reflation and inflation on profit margins. In short, what began as an optimal investment environment, due to low and stable inflation, accommodative monetary policy and supply-side tax reform, led to the Great Inflation and economically devastating decade of the ‘70s in large part due to policy errors and policymaker hubris.

Inflation came into the ‘60s as a lamb, averaging 1.3% for the first half of the decade, but went out like a lion at 4.2% for the second half. Alongside the increase in consumer price inflation, nominal wage growth accelerated as well. President Reagan later called inflation “the thief in the night”, however in the reflation regime of the early ‘60s the topic had not yet reached political toxicity due to the illusion of higher nominal wages. By the end of LBJ’s presidency, the disciples of ‘new economics’, who did not differentiate between the supply and demand effects of fiscal policy, were raising taxes and discouraging capital investment to slow inflation rather than slowing their spending on ‘guns and butter’. The transition from reflation to inflation was complete.

The Road to Bretton Woods II?

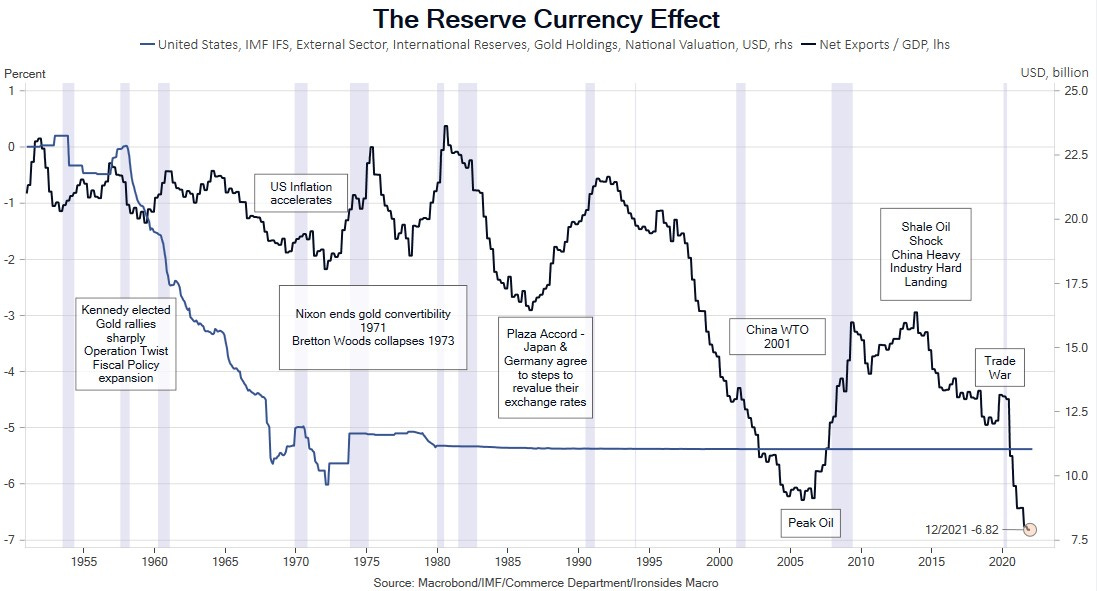

The previous section was intended to highlight the effects of the current US policy regime, given the similarities to the early ‘60s on domestic growth and markets. There was another issue that added complexity to the policies of the Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon Administrations, the Bretton Woods currency agreement that had evolved into the dollar gold standard. The Kennedy Administration coerced the Martin Fed into ending their ‘bills only’ open market operations policy to expand the monetary base without losing gold, but it failed. The global situation was like the current environment: Japan and Germany had recovered and were running considerable trade surpluses, while refusing to adjust their exchange rates to offset the growing global imbalances. What was originally intended as a flexible exchange rate regime was anything but, as mercantilist tendencies penalized the US and UK.

One of the strongest arguments for the dollar remaining the world’s reserve currency is expanded federal borrowing capacity. However, from the January 5th Georgia elections through the signing of the $1.9 trillion American Recovery Plan in March, long-term real rates (TIPS yields), the part of the market least influenced by Fed asset purchases, moved sharply higher, hinting the world’s reserve currency is approaching the limit of its borrowing capacity. The primary driver of exchange rate volatility during the pandemic was the US’s role as the dominant source of safe assets and trade credit that drove the dollar sharply higher, only to reverse as the pandemic panic receded. However, the pandemic and associated shock to global supply chains is likely to accelerate the deglobalization process that was well underway during the last cycle, even prior to the Trump Presidency. This will leave export dependent, current account surplus economies, ranked 2 (China), 3 (Japan) & 4 (Germany) in terms of GDP, with excess goods capacity and an associated incentive to depress their exchange rate relative to the dollar.

Despite the defeat of Donald Trump, the political pressure resulting from the US trade deficit remains acute. The Biden Administration is showing no signs of removing the China tariffs and signed an executive order to force purchases of US products in government contracts. Treasury Secretary Yellen’s economic ideology is likely supportive of the dollar remaining the reserve currency and is generally supportive of Ricardo’s comparative advantage and free trade, however she has been critical of China’s mercantilist policies. She is also a labor economist with similar economic ideology to the key economic figure in the Kennedy Administration, Walter Heller. Although the Biden Administration is intent on strengthening European relations, the size of Germany’s current account surplus and European non-tariff trade barriers are likely to remain a source of tension. In other words, while the US & China signed an agreement prior to the pandemic, the trade war and deglobalization trend are likely to persist at through the cycle, if not multiple cycles, and the dollar’s role as the reserve currency is at the nexus of this conflict. In the near term, notwithstanding our analysis that US monetary and fiscal policy are less efficacious than policymakers believe, US policy is likely to be more effective than that of our major trading partners. This implies that as the pandemic recedes, the dollar is likely to fall in 2021 due to looser effective fiscal and monetary policy.

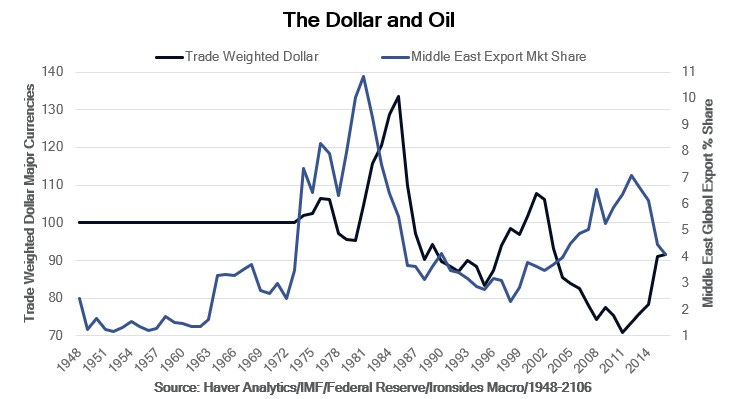

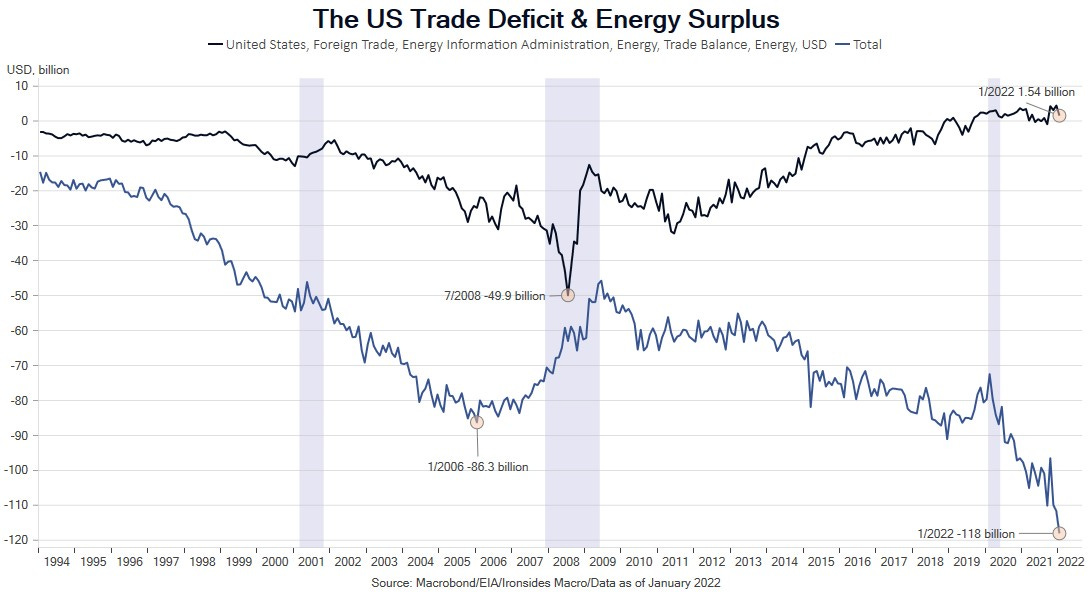

Given our expectations for a reversal in the secular disinflationary trend as deglobalization eases pressures on the primary deflationary impulse, tradeable goods prices, combined with a policy regime reminiscent of the early ‘60s that led to the Great Inflation, we spent time researching the demise of Bretton Woods. We extracted quotes (see below) from two papers that captured flaws in the system. The Triffin dilemma or Triffin paradox, the conflict between short-term domestic and long-term international objectives for countries whose currencies serve as global reserve currencies, was the crucial issue in the ‘60s and we suspect will be problematic in the ‘20s. Milton Friedman and later John Taylor’s policy prescriptions were floating exchange rates and a domestic monetary rules-based system, the antithesis of the views of the authors of Bretton Woods original architecture (John Maynard Keynes & Harry Dexter White). The Kennedy and the Johnson Administration were elected with mandates to focus on domestic policy, and that shift in policy focus was initially positive for growth and domestic equities. But after 1965, Johnson’s Great Society and the Vietnam War turned reflation into inflation and the gold dollar Bretton Woods system became unstable. With classic economic liberalism in the minority amongst policymakers in the ‘2020s, another currency agreement combined with more discretionary monetary policy is a possibility if the pressures of deglobalization intensify as we expect. One of the flaws of Bretton Woods was a fixed gold price that suppressed US inflation for a decade, only to lead to explosive inflation when the price constraint was removed. Our chart of the post-WWII US trade deficit is intended to suggest that as the world’s reserve currency, for the world to have a sufficient supply of dollars, the US needs to run persistent current account deficits. This became untenable over the last two decades as it led to what David Autor calls The China Shock and certainly contributed to the election of Donald Trump in 2016. One of the early catalysts for a widening current account deficit in the late ‘60s and ‘70s was the growing US energy trade deficit. The shale revolution ended this deficit, raising the possibility that the dollar could become a petrocurrency, an outcome that would be troubling for large oil importing economies including China, Japan and Germany (oil shocks could be exacerbated by an associated increase in the dollar).

With the US likely to pursue inflationary fiscal and monetary policies like in the ‘60s which ultimately led to the demise of Bretton Woods, the rise of digital gold may represent the canary in the coal mine for the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. It is important to note that the full convertibility Bretton Woods period from 1959-1970 began as a period of inflation and growth stability across the developed world. It was not until US inflation accelerated that the system collapsed. Consequently, our deep dive into Bretton Woods was intended to provide a longer-run road map for the global currency regime and a framework for crypto currencies potentially playing a role in global trade in the ‘20s. If we follow progress from reflation to an inflationary regime, well before the world spontaneously adopts a ‘bitcoin standard’, global policymakers will attempt another currency regime, something like a Bretton Woods II.

“The system that operated in the next decade (‘50s) turned out to be quite different from what the architects had in mind. First, instead of a system of equal currencies, it evolved into a variant of the gold exchange standard-the gold dollar system.”

“The second important difference between the convertible Bretton Woods system and the intentions of the articles was the evolution of the adjustable peg system into a virtual fixed exchange rate system. Between 1949 and 1967, there were very few changes in parities of the G10 countries. The only exceptions were the Canadian float in 1950, devaluations by France in 1957 and 1958, and minor revaluations by Germany and the Netherlands in 1961. The adjustable peg system became less adjustable because, on the basis of the 1949 experience, the monetary authorities were unwilling to accept the risks associated with discrete changes in parities-loss of prestige, the likelihood that others would follow, and the pressure of speculative capital flows if even a hint of a change in parity were present.”

“In sum, the problems of the interwar system that Bretton Woods was designed to avoid reemerged with a vengeance. The fundamental difference, however, was that the system was not likely to collapse into deflation as in 1931 but rather explode into inflation. “

The Bretton Woods International Monetary System: A Historical Overview (nber.org), Michael D. Bordo

“Truly independent central banks are fair‐weather institutions. When there is any serious conflict between the policies they favor and policies strongly favored by the central political authorities—generally reflected through Treasury policy—the political authorities have inevitably had their way, though at times only after some delay.”

“Friedman also thought that the combination of flexible exchange rates and a domestic monetary rule was more consistent with democratic principles than a regime based on fixed exchange rates and discretionary monetary policy.”

Milton Friedman and the Case for Flexible Exchange Rates and Monetary Rules, Cato Institute

“Where could Bitcoin be in another seven or so years? The report notes the advantage of Bitcoin in global payments, including its decentralized design, lack of foreign exchange exposure, fast (and potentially cheaper) money movements, secure payment channels, and traceability. These attributes combined with Bitcoin’s global reach and neutrality could spur it to become the currency of choice for international trade.”

Bitcoin At the Tipping Point, Citi Global Perspectives & Solutions

Additional Sources:

“A History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 2, Book 1, 1951-1969”, Allan H. Meltzer

“Clashing Over Commerce, A History of US Trade Policy”, Douglas A. Irwin

“1931, Debt, Crisis and the Rise of Hitler”, Tobias Straumann

“The Denationalisation of Money’, F.A. Hayek

“Great Society, A New History”, Amity Shlaes

“The Bitcoin Standard, The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking”, Saifedean Ammous

Barry C. Knapp

Managing Partner

Director of Research

Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC

908-821-7584

bcknapp@ironsidesmacro.com

https://ironsidesmacro.substack.com

https://www.linkedin.com/in/barry-c-knapp/

@barryknapp

This institutional communication has been prepared by Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC (“Ironsides Macroeconomics”) for your informational purposes only. This material is for illustration and discussion purposes only and are not intended to be, nor should they be construed as financial, legal, tax or investment advice and do not constitute an opinion or recommendation by Ironsides Macroeconomics. You should consult appropriate advisors concerning such matters. This material presents information through the date indicated, is only a guide to the author’s current expectations and is subject to revision by the author, though the author is under no obligation to do so. This material may contain commentary on: broad-based indices; economic, political, or market conditions; particular types of securities; and/or technical analysis concerning the demand and supply for a sector, index or industry based on trading volume and price. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author. This material should not be construed as a recommendation, or advice or an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any investment. The information in this report is not intended to provide a basis on which you could make an investment decision on any particular security or its issuer. This material is for sophisticated investors only. This document is intended for the recipient only and is not for distribution to anyone else or to the general public.Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although such information is believed to be reliable, no representation is made is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of such information. This information may be subject to change without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics undertakes no obligation to maintain or update this material based on subsequent information and events or to provide you with any additional or supplemental information or any update to or correction of the information contained herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates and partners shall not be liable to any person in any way whatsoever for any losses, costs, or claims for your reliance on this material. Nothing herein is, or shall be relied on as, a promise or representation as to future performance. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS.Opinions expressed in this material may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed, or actions taken, by Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates, or their respective officers, directors, or employees. In addition, any opinions and assumptions expressed herein are made as of the date of this communication and are subject to change and/or withdrawal without notice. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may have positions in financial instruments mentioned, may have acquired such positions at prices no longer available, and may have interests different from or adverse to your interests or inconsistent with the advice herein. Ironsides Macroeconomics or its affiliates may advise issuers of financial instruments mentioned. No liability is accepted by Ironsides Macroeconomics, its officers, employees, affiliates or partners for any losses that may arise from any use of the information contained herein.Any financial instruments mentioned herein are speculative in nature and may involve risk to principal and interest. Any prices or levels shown are either historical or purely indicative. This material does not take into account the particular investment objectives or financial circumstances, objectives or needs of any specific investor, and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, investment products, or other financial products or strategies to particular clients. Securities, investment products, other financial products or strategies discussed herein may not be suitable for all investors. The recipient of this report must make its own independent decisions regarding any securities, investment products or other financial products mentioned herein.The material should not be provided to any person in a jurisdiction where its provision or use would be contrary to local laws, rules or regulations. This material is not to be reproduced or redistributed to any other person or published in whole or in part for any purpose absent the written consent of Ironsides Macroeconomics.© 2021 Ironsides Macroeconomics LLC.